Two authors, Patricia Cornwall and Shirley Harrison, tried to unmask Jack the Ripper. Ms Harrison’s candidate is James Maybrick and Ms Cornwall’s candidate is Walter Sickert, whom she also linked to the Thames Torso Murders, a contemporary of Jack’s Whitechapel murders in London in the late 1800’s.

A person can be profiled by analysing the product of their imagination – what they create either in art or literature, is a projection of their inner thoughts and emotions. Psychological tests work on the same principle as it provides a sample of the person’s inter- and intra-relationships and their perception and internal organization of the world. I have often compiled profiles of stalkers and blackmailers based upon their threatening letters and psychologists analyse children’s drawings to identify lurking pathology.

Shirley Harrison’s Candidate

In author Shirley Harrison’s (1998 / 2010)book, The Diary of Jack the Ripper, the Chilling Confessions of James Maybrick she tells the story of how the diary of James Maybrick, a cotton merchant from Liverpool, was discovered in 1991 and the references therein strongly suggests him being Jack the Ripper. Ms Harrison’s book also contains the famous Ripper letters sent to the Scotland Yard investigators, showing some resemblance between the letters and James Maybrick’s diary.

Ms Harrison and the current owner of the diary, Mr Robert Smith argue that scientific methods have established that the book and ink used dates from the 19th century; that the symptoms of arsenic addiction, accurately described in the diary were known to very few persons; that some details of the murders mentioned in the diary were known only to police and the Ripper himself; and that one of the original crime scene photographs shows the initials “F. M.” on a wall behind the victim’s body written in what appears to be blood. These, they claim, refer to Florence Maybrick, James’s wife, whose possible affair was the purported motivation for the murders.

Complimentary to the diary, in June 1993, a gentleman’s pocket watch, made by William Verity of Rothwell in 1847 or 1848, was found and has “J. Maybrick” scratched on the inside cover, along with the words “I am Jack”, as well as the initials of the five canonical Ripper victims.

I attended and lectured at a serial killer conference at Liverpool University in 1998 where I met Ms Harrison personally and held the original ‘Jack the Ripper diary‘ in my hands – it was a memorable experience.

Who was James Maybrick?

James Maybrick was born in Liverpool in 1839 and became a cotton merchant, whose business required him to travel regularly to the United States and in 1871 he settled in Norfolk, Virginia. Then he contracted malaria, which was at that time treated with a medication containing arsenic and he became addicted to the drug. In 1880, 42-year-old James returned to the company’s offices in Britain and met his future wife, 18-year old Florrie, on the voyage. The couple returned to Liverpool to live at Maybrick’s home, “Battlecrease House” in Aigburth, a suburb in the south of the city. James regularly travelled to London for business and was purported to have lodged close to the Whitechapel murder scenes.

James Maybrick’s health took a turn for the worst on 27 April 1889, and he died 15 days later at his home Battlecrease House. Florrie was suspected and arrested and later convicted of his murder. She spent 15 years in prison and then returned to America where she lived in obscurity until her death.

Patricia Cornwall’s Candidate

In her 2003-book Portrait of a Killer Jack the Ripper Case Closed fictional crime author Patricia Cornwall poses the hypothesis that Jack the Ripper was none other than Walter Sickert the artist, based upon her analysis of some of his paintings; that he used the same paper as the Ripper letters; that he had a deformed sexual organ (which according to her could explain his anger at prostitutes) , and she even managed to obtain DNA ‘evidence’. To her great dismay, Ms Cornwall discovered that the police also used the same paper than what was used in the Ripper letters.

Before Ms Cornwall, already in 1976 Stephen Knight, in his book Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, and Jean Overton Fuller, in her 1990-book Sickert and the Ripper Crimes both linked Walter Sickert to Jack the Ripper.

Who was Walter Sickert?

Walter Sickert was born in Germany in 1860 and became a British Post Impressionist artist. Sickert’s perchance for painting music halls, dancers and singers, like his Katie Lawrence at Gatti’s indicate his interest in sexually provocative themes. He subjects were considered tawdry and vulgar. I have not seen all of Sickert’s paintings myself, and must admit there are some provocative ones, especially the Camden Town Murder series. On 11 September 1907, a prostitute named Emily Dimmock’s throat was slit in her home at St Paul’s Road, Camden. The murder case caused great sensationalism in the press. Sickert renamed several of his previous paintings of naked women lounging on beds, after the Camden Town Murder, yet none of the paintings were violent. Sometime between 1905 and 1907, Sickert lodged in a room, which the landlady had told him had previously been occupied in 1881 by a person she believed to have been Jack the Ripper. Sickert painted “Jack the Ripper’s bedroom” around this time.

Strong evidence shows that Sickert, an acquaintance of Impressionist Degas, was in France at the time of Jack the Ripper’s Whitechapel murders.

Besides being Jack the Ripper, Ms Cornwall also claims Walter Sickert could be the Thames Torso murderer, a contemporary of Jack the Ripper.

Most people who are interested in serial killers are quite familiar with Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel murders, but in short here is a summary: From August until November 1888 the mutilated bodies of five prostitutes were discovered within a range of a mile of each other in Whitechapel, London. The modus operandi revealed deep slash wounds to the throat, followed by extensive abdominal and genital-area mutilation, the removal of internal organs, and placing them over the victim’s shoulders and progressive facial mutilations.

The canonical five victims of the Whitechapel murders attributed to Jack the Ripper are: 31 August 1888: Mary Ann Nichols; 8 September 1888: Annie Chapman; 30 September, 1888: Elizabeth Stride; 30 September 1888: Catherine Eddowes and 9 November 1888: Mary Jane Kelly.

Less people are familiar with the Thames Torso murders: The canonical four of the Thames Torso Murder series were the Rainham Mystery, the Whitehall Mystery, the murder of Elizabeth Jackson, and the Pinchin Street Torso Murder, discussed here separately:

Between May and June 1887, dismembered parts of a woman’s body were found in the Thames near Rainham. Several body parts were discovered on different days, all except the head and upper chest of the woman.

On 11 September 1888 on the banks of the Thames at Pimlico, a right arm and shoulder were discovered. By 17 October, more limbs of the same body were found at different sites in the centre of London, including the torso, On 17 October 1888 reporter Jasper Waring obtained the permission form the police to inspect the construction site of Scotland Yard’s new headquarters on the Thames Embankment, and with the help of a dog, found a left leg, cut above the knee, buried at the site.

On 4 June 1889, a torso was found in the Thames and over the next few days more limbs were found at Battersea, Nine Elms, Wandsworth, Limehouse, Bankside and the Chelsea Embankment. The woman had been dead no more than 48 hours, and she was eight months pregnant. Although her head was never found, she was identified as Elizabeth Jackson, a homeless prostitute from Chelsea.

On 10 September 1889, the headless and legless torso of an unidentified woman under a railway arch at Pinchin Street, Whitechapel. She was not killed on the scene. The victim’s abdomen was extensively mutilated in a manner reminiscent of Jack the Ripper, however her genitals had not been mutilated.

One must take into consideration that by October 1888, London’s Metropolitan Police Service estimated that there were 62 brothels and 1,200 women working as prostitutes in Whitechapel. Besides the Jack the Ripper-Whitechapel and the Thames Torso murders, there were several other vicious murders of prostitutes. Sadly, they are easy targets.

The Tools of Modus Operandi and Signature.

Despite the similarities in victim selection and the geographical locations of the contemporary murders, a forensic profiler using the tools of modus operandi and signature can determine whether these murders were committed by the same person. Determining modus operandi is the job of detectives – how was the murder committed. Determining signature is the job of the psychological profiler – what are the hidden motivation and idiosyncratic identifiers of the killer. Any unusual behaviour on a crime scene, symbolic or compulsive acts, are called personation. When personation is repeated, it becomes signature. Who-ever killed the women did not have to disembowel or dismember them to kill them – that is signature.

There is a major difference between disembowelment committed during the Jack the Ripper Whitechapel murders and dismemberment applied in the Thames Torso murders. Disembowelment is the chaotic, messy removal of intestines and sexual organs in the case of Jack’s victims and points to a disorganized mind. Dismemberment or dissection is precise and takes time. It points to an organized mind. Jack’s victims were left where they were killed. The limbs of the Thames Torso murders were transported and distributed over a period of days – this also indicates planning and concealment.

One of the victims who was dismembered in the Thames Torso case, was a well-educated woman. Why would Jack suddenly change his modus operandi of disembowelling prostitutes to dissecting a well-educated woman? An organised murderer can degenerate and become disorganized, but a disorganised murderer cannot upgrade to become organised.

Coincidently in James Maybrick’s diary it is demonstrated how his mind was rapidly deteriorating, illustrated by his handwriting and his thought processes systematically and incrementally degenerating due to arsenic abuse. In contrast, Sickert was a highly intelligent perfectionist, whose memory only deteriorated near the end of his life in his 80’s

Serial killers do not suddenly become tired of killing and retire. They will start up again after release from prison and continue until they die – Andrei Chikatilo was still killing after 20 years. Sickert was 28 years old at the time of Jack the Ripper’s murders. He lived until the age of 83. No more Whitechapel murders were committed after the death of James Maybrick in 1889.

The cases remain open, neither Jack the Ripper, nor the Thames Torso murderer have been identified, despite the numerous attempts at amateur forensic profiling. If I had to choose between Walter Sickert, the artist and James Maybrick the cotton merchant, my bet would be James Maybrick, based on modus operandi and signature, but as I said, the case is not closed.

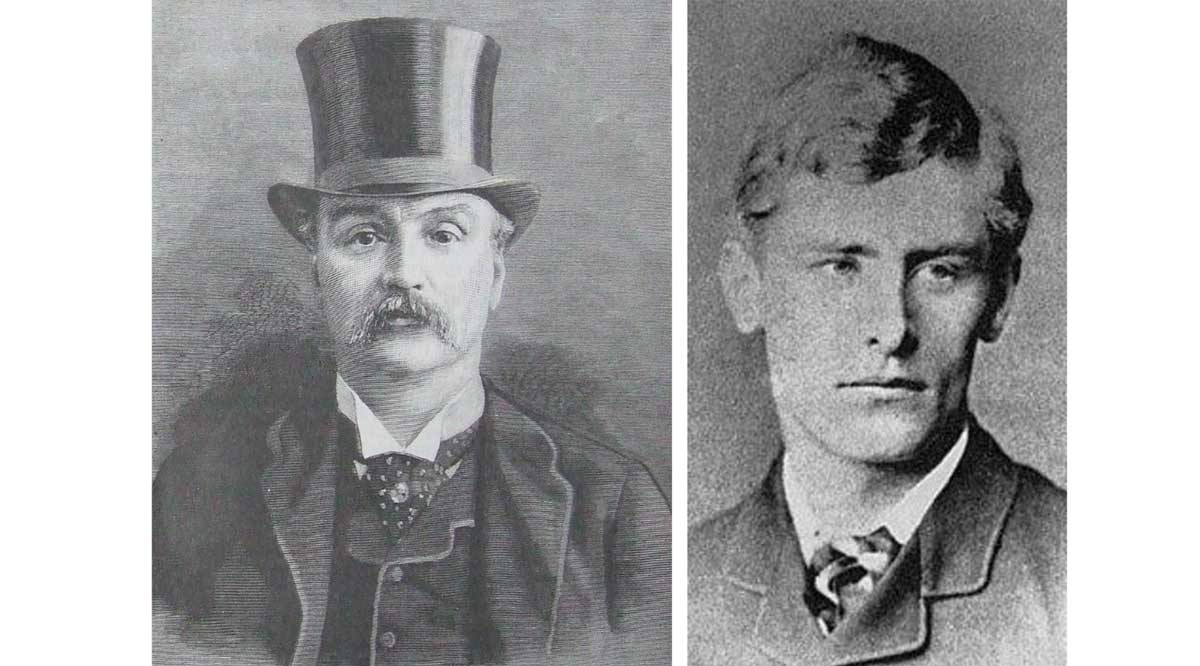

Top image: James Maybrick. Illustration for The Graphic, 24 August 1889 (Public Domain) and Walter Sickert (1884) (Public Domain)