General research on Black Widow killers concur they commence their criminal careers at the age of 25 years, and target spouses, partners, family members, their children and anyone they might have formed a personal relationship with. They may kill someone threatening to expose them. They are quiet killers and go undetected for long periods because no-one suspects them. Their preferred weapon of choice is usually poison and the main motive is profiting from insurance policies and inheritances – fitting my theory on Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, that these women substitute money for safety – the second tier of basic needs.

Dubbed South Africa’s first female serial killer, Daisy de Melker has become not only an urban legend, but unlike Letitia Erasmus, she attained world acclaim, and her case would have gone viral on social media if it played out today, but it happened during the 1920’s and the 1930’s, between the two World Wars. Gold had been discovered on the Reef in South Africa in 1886, resulting in the Boer Wars, which lasted from 1889 to 1902 and in 1910 South Africa became a Union.

Daisy Louisa Hancorn-Smith was born on 1 June 1886 at Seven Fountains, near Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape. Her siblings consisted of six other sisters and four brothers. At the age of ten, Daisy was sent to Bulawayo in then Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe), to live with her father and two brothers who had settled there. There were rumours that she could have been molested either by her father or brothers, but these have not been confirmed. One can only surmise that Daisy, being one of 11 siblings, did not grow up in a wealthy family. At the age of 13 she was sent to boarding school at the Good Hope Seminary in Cape Town. Daisy was a bright pupil and had a high intelligence. In 1903 she returned to Bulawayo for a short while and then returned to be trained as a nurse at the Berea Nursing Home in Durban. She was educated in medicine, drugs, administering hypodermic syringe and surgery. On vacation back in Rhodesia she met, fell in love with and got engaged to Bert Fuller, but tragedy struck when Bert died of Blackwater fever on their supposed wedding day in October 1907. Shortly after, Daisy inherited an amount of a hundred pounds from her deceased fiancé.

Daisy relocated to Johannesburg, which was just developing as a miner’s town after the discovery of the gold reef in 1886, and she lived with her aunt. There she met William Alfred Cowle, a plumber working for the Johannesburg City Council. He was 14 years older than Daisy. They got married on 3 March 1909. William was not a wealthy man, but he was a member of the pension fund and he provided Daisy the stability she had been missing in her life.

They lived in a modest house in Turffontein. Turffontein was south of the mine belt and mostly mine workers lived there – it had a distinct working-class flavour. The town’s swirling dust storms and the interminable pounding of its stamp mills drove the more fastidious mine bosses and magnates to move northwards. For 14 years Daisy lived in Turffontein with her husband Alf and the couple had five children. The first two were twins who died in infancy; their third child died of an abscess on the liver; and the fourth suffered convulsions and bowel trouble and died at 15 months old. But their last son Rhodes Cecil, born on 21 June 1911, survived.

Alf was a sickly man and Daisy often informed their neighbours that he suffered from stomach cramps. On the morning of 11 January 1923, Alf went to the kitchen and drank a glass of Epsom salts. He took his lunch box and set off for work. Before he reached the front door, he doubled up with pain. Daisy put her husband to bed and called Dr Fourie, who diagnosed a nerve condition. Later that day, Daisy called her neighbours anxiously, telling them that Alf was dying. Dr Fourie returned to find Alf dead. He diagnosed cerebral bleeding and the cause of death was kidney failure. Daisy, a widow of 37, inherited the sum of 1,800 pounds as well as the house.

Three years later on 1 January 1926, she married Robert Sproat, a 46 year old bachelor. Like Alf, Robert was much older than Daisy – fitting the typology of a woman deprived of basic safety needs seeking a wealthy protector, as described by Abraham Maslow.

Robert had also been a plumber at the City Council, but he had an extra income due to his clever investments. He had a pension plan, assets, shares and stocks. Daisy moved up in life and they relocated to Terrace Street, in Bertrams, Johannesburg.

One Sunday evening in October 1927, Robert became violently ill after Daisy had given him a glass of beer. Dr Fourie was summoned again and suspected that Robert had a bleeding ulcer, or maybe arteriosclerosis, or maybe he suffered from cerebral bleeding as well. Dr Fourie was uncertain, but he prescribed medication. Robert asked Daisy to call his friend, William Johnston to his bedside. He told William to make sure that Daisy inherits everything, since his will was still in favour of his mother in England. This upset Daisy tremendously. She summoned Robert’s brother, William, from Pretoria, who arrived the following day. She asked William to convince Robert to draw up a will in her favour. William did not want to discuss the issue of a will with his ailing brother. A little later Daisy presented Robert with a will that she had drawn up. With a trembling hand, Robert signed the will, with William and a neighbour as witnesses. Remarkably he recovered from his illness after that.

But not for long. On 5 November 1927, poor Robert fell ill again. The doctor diagnosed cerebral bleeding. Scarcely had the diagnoses been made, when Robert breathed his last. Daisy inherited 5,000 pounds from her husband. Her insatiable greed led her to make a mistake. She had the gall to write to her mother-in-law in England, complaining that there was not enough money to cover the funeral costs, and would Mrs Sproat be so kind to contribute to her son’s funeral. Mrs Sproat senior referred this letter to her surviving son, William, who furiously confronted Daisy and warned her to stay out of their lives. Daisy obliged.

Daisy spent money on buying a car and a motorbike for her son Rhodes. They also went on an overseas trip. Then she enrolled Rhodes at the prestigious Hilton College. Yet, Daisy had other problems with her son, who was 16 by this time. He was a lazy spoilt boy. After school he completed an apprenticeship as a plumber. Rhodes was more interested in partying and riding his motorbike, than working. Daisy found him work in Rhodesia, which he quit and again in Swaziland, where he contracted malaria. Rhodes did not realise that his mother had taken out an insurance policy on his life when he was 11. The policy was to pay out when he reached the age of 21.

Whilst in Swaziland, Rhodes received the news that his mother was to become Mrs Sidney Clarence de Melker on 21 January 1928. Sidney de Melker, was originally a plumber from Kimberley, but he was also a Springbok rugby player from 1903 to 1907. The couple moved to Simmer East Cottages in Germiston.

The couple were popular – Sydney because he was a former Springbok rugby player and Daisy because she had a magnetic personality. Most people who met her could not resist her vivaciousness. Men fell over their feet to gain her attention. Sydney considered himself lucky to be chosen by her.

In 1931 Rhodes returned home, gravely ill with malaria. His mother nursed him diligently. He repaid her kindness by assaulting her twice. Daisy had had enough of her son, who spent her “hard-earned” money without a second thought. She found him another job at a garage. On 2 March 1932 he grabbed his lunch box and a flask of coffee and set off to work. By three o’ clock that afternoon he complained of a stomach ache. Yet he decided to practise rugby hoping that the pain would cease. That night he went to bed, but woke up in the middle of the night again from the pain. Rhodes had to get up the following day since he was charged to appear in court regarding a traffic violation. He paid the fine and went to work, feeling very ill. By three o’ clock his boss sent him home. Daisy put her son to bed. At six o’ clock she gave him a glass of ginger beer and wished him a good night. Rhodes never woke up again. The cause of his death was ascribed to malaria. Daisy inherited the hundred pounds of his life insurance. It was three months to his 21st birthday.

When William Sproat, who had quietly been keeping tabs on his ex-sister-in-law, heard about Rhodes’ death he went straight to the police and informed them about the similarities concerning the three deaths. The police took notice and on 15 April 1932 the three bodies were exhumed at the New Brixton Cemetery. Daisy’s first two husbands, Alf and Robert were buried on the same plot as Rhodes and shared a gravestone. Forensic analyses indicated that both William and Robert had been poisoned with strychnine and Rhodes with arsenic. Daisy de Melker was promptly arrested for murder.

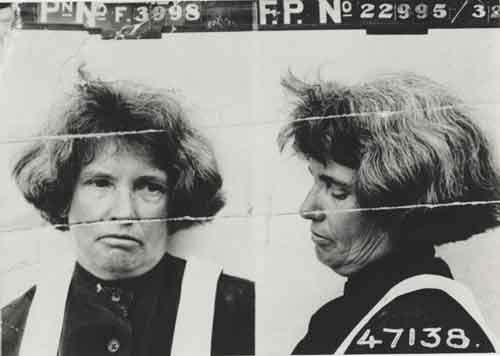

The trial commenced on 17 October and lasted until 25 November 1932. Advocate Harry Morris defended Daisy, who was supported by her husband Sydney de Melker throughout the ordeal. Crowds queued outside the court house to find a seat and the trail made international news headlines. Daisy often waved at the crowds when she entered court. She was writing a movie script about her life in prison.

During the trial the prosecution, led by Cyril Jarvis for the Crown, had a problem. Despite intensive police investigations, no-one could find poison in her home, nor could they trace the origin of where the poison was bought. Without this, they had no hard evidence that Daisy was responsible for the murders, no matter how suspicious the circumstances. At this stage the newspapers had a field day with the trial of Mrs Daisy de Melker, but no-one had a photograph of her. Luckily at last the Star newspaper obtained a photograph and published it.

Mr Abraham Spilken of Spilken Pharmacy in Turffontein looked at the photograph and not only recognised the by now notorious Mrs Daisy de Melker as the same Mrs Daisy Sproat, whom he had known before but also who had recently bought arsenic from his pharmacy. In secrecy he went to the police. Daisy had visited his shop on 25 February 1932, he said, and bought sixty grams of arsenic. She signed her name as Mrs Sproat from Terrace Road. Daisy told him she had remarried and she needed the poison for a cat. At that stage he did not know that she was actually Mrs De Melker.

Abraham Spliken was introduced as a surprise witness. The moment he took the stand, Daisy’s expression changed from the customary smirk to deep concern.

Mr Justice Greenberg finally found that the Crown could not prove beyond reasonable doubt that Daisy had administered the poison to her husbands, but before her smile grew too wide, he found her guilty of the murder of her son and sentenced her to death by hanging.

Daisy de Melker was hanged on 30 December 1932 at the age of 46. Even on the gallows, she proclaimed her innocence. Could she have been?

Innocent or Guilty?

Author Lenor Tancred in her book Daisy de Melker, Innocent or Guilty provides a compelling argument that Daisy may not have been guilty. I had the privilege of interviewing her in 2024.

Lenor based her research on the primary transcripts of the trial – the original documents. Her first argument is that the forensic pathology examinations were botched. Forensic pathology was still crude in the 1930’s and they did not have the sophisticated technology available today. The pathologists grouped all the organs together for testing, not separating hair from intestines and brain matter. Defence advocate Harry Morris had a field day in shredding the evidence of Crown’s witness Dr J.M. Watt, an expert toxicologist and professor of pharmacology at Witwatersrand University to ribbons.

Lenor’s account on the living conditions of southern Johannesburg concurs with the general knowledge. Turffontein was south of the mine belt. The mine dumps were covered with cyanide residue and not rehabilitated with grass. Windstorms that blew dust storms all over the area were so bad the affluent relocated to the northern suburbs. The southern suburbs were therefore infiltrated with cyanide laden dust particles, which often caused convulsions in children – as Daisy’s children had died of.

Lenor points that both husbands were plumbers. Plumbers apprentice at the age of 16 and by the time of these men’s deaths, they had been exposed to lead fumes and poisoning for many years and it would show up in their autopsies. Plumbers used lead for soldering pipes.

Both Alf and Robert had not been healthy men. Robert had been medically boarded by the time he married Daisy. The two men shared three physicians between them. Both men were addicted to over-the-counter medication. Arsenic and strychnine were pharmaceutical components of over-the-counter medicine at that time. Arsenic precipitates to the bottom of the bottle and if not shaken regularly, a last dose could therefore be lethal.

The vertebrae of the husbands showed signs of pink strychnine – an industrial form of strychnine. The Crown was desperate to link Daisy with poison. It was even brought before court that as a young woman Daisy had bought strychnine in Rhodesia. Daisy was a teenage girl of around ten to 12 years of age in Rhodesia. It is a preposterous argument that at the age of 12 she would buy poison to kill future husbands and her son, whom she had never even met or conceived. Daisy was not found guilty of the murders of her husbands due to lack of evidence – perhaps there was no evidence.

Regarding her son Rhodes, Lenor points out that he had contracted malaria. A year before his death, he was extremely ill and Daisy had nursed him back to health. At that time malaria was not curable and the medication involved an arsenic based product, which would accumulate in the body. By then there was already a life insurance policy, yet Rhodes survived.

The Crown proposed that Daisy had put arsenic in Rhodes coffee flask before he went to work on that fateful morning of 3 March, yet this is circumstantial for there is no evidence that she administered arsenic to the flask. According to Lenor, the court records did not indicate that there was indeed poison in the flask. Arsenic is virulent and fast working, yet Rhodes still participated in a rugby practice that afternoon. Rhodes’ colleague, James Webster had also drunk some of the coffee and was purported to have had stomach cramps, and traces of arsenic were found in James’ hair and fingernails – yet Daisy was never charged with attempted murder of James. Arsenic at that stage was a component of shampoo’s, face wash, soap and washing powder.

The chemist Dr Spilken’s testimony must have come as manna from heaven to the prosecution. Yet Lenor argues there is a reasonable argument why Daisy signed the poison register under the name of Mrs Sprout. Daisy still received mail in the neighbourhood where she had previously lived and on one of her trips to collect the mail, she went to the chemist, where she was well-known, to buy the poison – for a stray cat! She signed her name as Sprout, for that was the name she was known as in that neighbourhood. Why would a murderess sign a name she was well-known for in a poison registrar, at a chemist who knew her well, if she planned a murder? Why not buy poison at an unknown chemist under a false name?

Daisy was convicted upon the evidence that she had bought the arsenic. This is purely circumstantial. Lenor believes if Daisy had been on trial today, the outcome might have been different. Daisy de Melker is believed to haunt several locations including her home, the women’s prison at what is today Constitutional Hill in Johannesburg, the High Court in Johannesburg and the South African Police Heritage Museum in Pretoria.

Rosemary Ndlovu

Dethroning Daisy de Melker as South Africa’s most prolific female killer is Rosemary Ndlovu, a South African police officer, who graduated to become a Black Widow serial killer. Rosemary personifies my warning that women can be as calculating and cruel as men, even if they wear uniforms. South Africa’s male serial killers cops were Phineas Tshitaudzi (1959), Louis Van Schoor (1989) and Kobus Geldenhuys, (1991) and Rosemary Ndlovu, now joins their ranks as a woman.

Nomia Rosemary Ndlovu was born in 1978 as one of seven siblings. Not much is known about her childhood years, except that her biological father passed away, probably at a young age for Rosemary and her sister Audrey had taken on the surname of their stepfather, Ndlovu. They were very poor. Rosemary was described as an intelligent quiet pupil, who would assist her mother working in the fields after school. Her siblings all remember her wanting to become a police officer since she was a child. Perhaps Rosemary’s subconscious need for safety – deprived by the passing of her father who was supposed to be her provider and protector, and their dire poverty – was the motivation for her to become a policewoman. Police officers are supposed to protect the vulnerable – to keep the community safe. They also earn steady salaries, which may not be much, but it provides stability. Perhaps Rosemary thought she could replace her loss of a protector by donning the blue uniform, but she certainly did not join the police force to protect the vulnerable, as police officers are supposed to do. Her blue uniform became a sheep’s clothing, camouflaging the predator.

Rosemary’s modus operandi was to take out funeral policies on her family members and then pay hitmen to have them killed – sometimes she was personally involved or present. Funeral policies are designed to pay out almost immediately after a death, so the family could afford the funeral and reception, which is a major extended family affair in African tradition. Rosemary collected her money within a week of the insured family member’s demise and with this money she paid the hitmen and the instalments of other policies.

It is remarkable that she managed to get away with it for a period of six years – before she was eventually detected. Female serial killers are known as ‘quiet killers”. Rosemary managed to get away with the murders for a few years because the murder dockets were investigated at different police precincts and since the modus operandi was different, there was linkage blindage. But the common denominator was Rosemary, the cop. Eventually Sergeant Keshi Mabunda, who was investigating the murder of her boyfriend Maurice Mabasa, became suspicious, collected all the dockets and painstakingly began his investigation which culminated in the arrest of a ruthless Black Widow serial killer.

In March 2012 her cousin Madala Witness Homu was found beaten to death. Rosemary collected R137 643 funeral insurance as the sole beneficiary.

In June 2013, her sister Audrey was poisoned and strangled. Rosemary collected R717 421.17.

In 2014 when Rosemary was assigned to the Tembisa Police Station, she was implicated in the thefts of a R5 assault riffle as well as a pistol. The internal investigation did come to a conclusive ending.

In October 2015, Maurice Mabasa, her live-in boyfriend and father of her child, Makhanani, was found murdered with over 76 stab wounds – overkill indicates a personal hate. During their three-year relationship, Rosemary and Maurice had financial troubles and he wanted to leave her. She was obsessively jealous and feared him abandoning her. A month before his death he awoke one night to find the house on fire – Rosemary had evacuated the property with their baby. Bottles with petrol were discovered under Maurice’s bed, but he escaped unharmed. He did not open a case. A month later, he was beaten and stabbed to death. Rosemary had 16 policies on Maurice’s life, some forged. She collected R416 357. Their baby Makhanani was raised by Maurice’s mother.

In 2016 Rosemary’s niece Zanele Motha was found beaten to death and Rosemary received R119 840 .

In April 2017 after her two-year old toddler went to visit Rosemary, the toddler died. She was not charged with this murder.

By know Sergeant Mabunda had established that Rosemary had a gambling addiction and she was hunted by loan sharks – confirmed by her commanding officer, Colonel Boloka.

In 2017 William Mashaba, Rosemary’s nephew, was found shot dead. He was not robbed and the last number on his phone was Rosemary’s. She walked onto his crime scene while the officers were processing it. Sergeant Mabunda managed to block the payout of the insurance.

In January 2018 Brilliant Mashagu, Audrey’s son and Rosemary’s nephew was found beaten to death. Payouts if the insurance were blocked.

Rosemary had hired hitmen to kill her remaining sister and her mother, on whose lives she had taken out funeral policies. The hitmen had moral objections to killing a woman with five children who was still breastfeeding her youngest and an old lady, so they alerted Colonel Boloka. During an authorized sting operation, Rosemary instructed an undercover cop to sedate her sister and her young children and then to set the house on fire. She said insurance companies were not suspicious of a house in a village burning, but they would suspect foul play if her sister and her children were shot or stabbed to death. Like the Station Strangler, Rosemary had booked herself into a clinic for depression to create an alibi, but she had a day pass to accompany the hitmen to show them her sister’s house.

Rosemary was arrested in 2018. Her trial commenced in 2021. Her mother did not believe her daughter was a killer and supported her throughout the trial – typically female serial killers go undetected because family members cannot believe them capable of murder. Many people described her as friendly, but she had a short temper.

In court Rosemary was defiant, arrogant and showed no emotion, except for fake tears when State prosecutor Advocate Riana Williams discussed Maurice’s murder. She showed no remorse or regret and had organized unsuccessful hits on Sergeant Mabunda and Colonel Boloka from inside prison. Rosemary Ndlovu was convicted in November 2021 on six murders with life sentences running concurrently. In her testimony, my erstwhile colleague Luitenant-colonel Elmarie Myburgh testified that Rosemary had no prospects of rehabilitation and was a serial killer. The judge commended Sergeant Keishi Mabunda for excellent detective work and Advocate Riana Williams for prosecuting. I concur.

Interestingly, after her conviction, it was disclosed that in 1994, at the age of 18, Rosemary had married a man called Hand Khosa. A year later in 1995, their son Jaunty was born. At some stage Rosemary abandoned her husband and son to look for a better life in Johannesburg. Jaunty was raised by his paternal family. Then in 2004 Hand fell ill and Rosemary visited him in hospital. A day later he died. Rosemary then discovered that Hand had an insurance policy which would pay out to Jaunty when he turned 18. In 2005, Rosemary went to fetch her 13-year-old son to visit her. Scarcely in her care, he was admitted to hospital due to poisoning. A day after she took him home, Jaunty died and Rosemary became the beneficiary of the life insurance to a sum of R12 000. In total Rosemary collected a sum of almost R1,4 million by way of killersurance.

Comparing Rosemary and Daisy, both these women had multiple siblings and grew up in poverty. It is unknown at what age Rosemary lost her father, but her financial safety needs were not gratified and neither was Daisy’s. At the age of ten she was sent to join her father and older brothers on a remote farm in Rhodesia. By coincidence Daisy received a payout from the death of her fiancé, Bert Fuller – she did not plan this, but it could have planted the seed in her to consider it as a source of income. Rosemary only got wind of Hand’s insurance to be paid out to Jaunty, after Hand’s death. Could this have triggered the diabolical plan of insurance as easy income too?

Perhaps these two women experienced an empty void due to some form of abandonment by their father figure. Then by some trick of fate, coins unexpectedly dropped into that empty emotional piggybank, and the sound waves reverberated and bounced off the empty hollowness of the cavern, to such an extent that they had to kill time and again to try and fill that void.

Top image: Arachne, the Greek maiden who wove more beautiful than the goddess Athena, was turned into a spider. (Public Domain)

References:

Lenor Tancred (2008) Daisy de Melker, Innocent of Guilty? Goodreads

Naledi Shange (2023) Killer Cop: The Rosemary Ndlovu Story. Melinda Fergusen Books

Micki Pistorius (2012) Fatal Females, Women Who Kill Penguin