Capital punishment was abolished on 6 June 1995 in South Africa. Norman Simons, the Station Strangler was sentenced on 14 June 1995 to 25 years for the murder of Elroy van Rooi. It was converted to a life sentence by an Appeal court in 1998. In December 2008, Magistrate Marelize Rolle found prima facie evidence that he was probably responsible for at least 6 more of the total of 22 boys attributed to the Station Strangler’s victims. He was released on parole in November 2023.

On 5 December 1997 Moses Sithole, the Atteridgeville serial killer (37 murders) was sentenced to 2410 years in prison. In 1997 Christopher Mhlengwa Zikode, the Donnybrook serial killer (8 murders) was sentenced to 140 years in prison. On 23 February 1998, Stewart Wilken, alias Boetie Boer (7 murders) was sentenced to seven life sentences by Justice Chris Jansen, who commented had the death sentence been available to him, he would have applied it. Cedric Maake, the Wemmer Pan serial killer (27 murders) was handed 27 life sentences in 2000. Lazarus Mazingane, (17 murders) was handed 17 life sentences and an additional 780 years in prison in 2002. In March 2023 The department of Correctional Services’ spokesperson, Singabakho Nxumalo confirmed these serial killers’ applications for parole have been denied.

Sometimes even my mind boggles at the extent of cruelty humans can inflict upon each other, and history tells how these abominable acts were condoned by the state or self-appointed sovereigns.

Everybody is familiar with the history of burning witches and criminals – who often died by asphyxia or cardiac arrest before their flesh was consumed by the flames – but since antiquity the cruel ingenuity of torturers inspired astonishingly horrific measures to punish transgressors and prolong their agonizing and excruciating deaths, often to gratify the sadistic pleasures of their executioners.

Roasted Alive and Swallowing Molten Lead

According to legend the Celtic druids held Roman legionaries captive in wicker men baskets, and then set them alight, as sacrifices to their gods. Although Cicero, Tacitus and Pliny the Elder, commented on human sacrifice among the Celts, it is only Julius Caesar in his Commentary of the Gallic Wars, who ascribes this particular practice to the druids. There is a possibility that the wicker man baskets could have been Roman spin to fan fear and disdain among the Roman populace towards the vicious Celtic enemies and to justify the invasions of the Celtic lands. However, there may be truth to it as a much later comment is attested to in the 10th-century Commenta Bernensia, (or Bern scholia preserved in the Burgerbibliothek of Bern, Switzerland) referring to Lucan’s De Bello Civili’s epic poem Pharsalia, describing the Celts burning people in a wooden effigy as sacrifice to Taranis, god of thunder.

Diodorus Siculus, in his Bibliotheca Historica, tells of the Sicilian bull, a brazen bull invented by Perillos of Athens for Phalaris, the tyrant of Akragas, Sicily. Prisoners were manhandled into an opened latch on the side of the metal bull and then a fire was made under it, to slowly roast alive the victims trapped inside. Perillos told Phalaris that he had designed an acoustic device implanted inside the bull that would convert the victims’ pitiful wails into the ‘melodious of bellowings’ of a bull, to escape, along with incense, through the open nose of the brazen bull. Phalaris tricked Perillos into a demonstration, locked him inside the bull and lit the fire. However, Phalaris freed Perillos before he died, but then he threw him over a cliff. Phalaris himself was tortured to death in his own brazen bull when he was conquered by Telemachus. Three Roman emperors used the brazen bull to torture Christians. Hadrian roasted St Eustace and his family in a brazen bull; Domitian roasted Saint Antipas, Bishop of Pergamon in 92 AD and in 287 AD Diocletian roasted Pelagia of Tarsus. Some say the brazen bull was also only propaganda and the Catholic Church discounts the roasting of St Eustace.

Under old Hebraic law certain sexual offences are punishable by burning. In the Mishnah, the following manner of burning the criminal is described: “The obligatory procedure for execution by burning: They immersed him in dung up to his knees, rolled a rough cloth into a soft one and wound it about his neck. One pulled it one way, one the other until he opened his mouth. Thereupon one ignites the (lead) wick and throws it in his mouth, and it descends to his bowels and sears his bowels.” In effect, the person dies from being fed molten lead.

During the Middle Assyrian period, a woman of loose morals was not allowed to cover her head with a veil – as decorum prescribed for a modest married woman. “A prostitute shall not be veiled. Whoever sees a veiled prostitute shall seize her … and bring her to the palace entrance. … they shall pour hot pitch over her head.” In 88 BC, Mithridates VI of Pontus had molten gold poured down the throat of the captured Roman general Manius Aquillius and it is rumored that the Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus – who was accused of greed – came to a similar death in 53 BC, administered by the Parthians.

In ancient Rome Christians were punished by tunica molesta (Latin for “annoying shirt”). “The Christian, stripped naked, was forced to put on a garment called the tunica molesta, made of papyrus, smeared on both sides with wax, and was then fastened to a high pole, from the top of which they continued to pour down burning pitch and lard, a spike fastened under the chin preventing the excruciated victim from turning the head to either side, so as to escape the liquid fire, until the whole body, and every part of it, was literally clad and cased in flame.”

Close Confinement: Starved or Spiked to Death

Starving prisoners to death was a way of circumventing the deed of actually killing the victim, which could have affronted some deity. Romans entombed Vestal Virgins who committed sexual transgressions in the Campus Sceleratus alive to starve to death, for it would have been a mortal sin to actually execute a Vestal Virgin. Vestals were often used as scapegoats in times of Rome’s great crises, as their chastity was directly linked to Rome’s wellbeing. Three Vestals were accused of breaching their chastity: Oppia who was entombed alive and Tuccia, who proved her innocence by carrying water in a sieve. According to Pliny the Younger, Cornelia, who was entombed on the orders of Emperor Domitian, was also innocent.

Similarly, as if kept in a dungeon was not enough, some prisoners in medieval times were forced into an ‘oubliette’ – a claustrophobic dark hole where one could scarcely turn around, let alone lie down and it was accessible only by a hatch or trapdoor, such as found in Leap Castle and Warwick Castle, England. The word “obliette” derives from French meaning ‘to forget’ – as these prisoners were deliberately just forgotten in those dark holes and left to die.

Polybius (208 – c. 125 BC) in his Histories speaks of Nabis of ancient Sparta, who created an effigy in the image of his wife Apega. The automation, dressed in expensive clothing, had its arms outstretched. Nabis was able to manipulate the arms of the life size doll to close in on a victim, hugging the victim to its breast. However, the device’s arms, hands, and breasts were spiked with iron nails, crushing the body of its victim. Queen Apega approved of the device and was said to revel in dishonoring men by humiliating women belonging to the families of male citizens, who refused to pay tax.

Nabis’ iron Apega probably gave rise to the concept of an Iron Maiden – an iron cabinet with spikes attached to a hinged front and a spike-covered interior, used to entrap and pierce the victim, who is left to die. Or it could have been inspired by the death of Marcus Atilius Regulus by the Carthaginians, who according to Tertullian’s To the Martyrs, was packed into a wooden box, “spiked with sharp nails on all sides so that he could not lean in any direction without being pierced”. Professor Wolfgang Schild, a professor of criminal law history at the Bielefeld University, disputes the actual existence of Iron Maidens and has argued that those on display in museums were pieced together from artifacts to create spectacular objects intended for commercial exhibition.

Vivisepulture is the practice of being buried alive. Herodotus in Histories records that burying people alive was a Persian custom, which they practiced in order to appease the gods. Not only was this execution reserved for enemies, but it was also considered a general sacrifice to the gods: “ I have heard that Amestris, wife of Xerxes, having grown old, caused 14 children of the best families in Persia to be buried alive, to show her gratitude to the god who is said to be beneath the earth“. Tacitus, in Germania, records that German tribes tied those guilty of shameful vices to a wicker frame, pushed them face down into mud, and then buried them alive.

Infelix Lignum the Unfortunate Wood for Crucifixion

Herodotus claims the Greeks were generally opposed to performing crucifixions but made an exception with the Persian general Atrayctes in 479 BC, whom: “they nailed (him) to a plank and hung him up”. The Romans on the other hand were not averse to crucifixion. Seneca the Younger (4 BC – 65 AD) wrote: “I see crosses there, not just of one kind but made in many different ways: some have their victims with head down to the ground; some impale their private parts; others stretch out their arms on the gibbet.” Tacitus records that in Rome executions were carried out outside the Esquiline Gate.

After defeating Spartacus in the Gladiator War, (73 – 71 BC) Crassus crucified 6,000 of Spartacus’ followers and a year later in 70 BC according to Josephus, after the destruction of Jerusalem, Roman soldiers crucified Jewish captives by nailing them in different positions outside the walls of Jerusalem. According to Roman custom, if a slave was found guilty of killing his master, all of the slaves including women and children would be crucified.

A cross could consist of a single stake, or a vertical beam (stipe) to which the horizontal beam (patibulum) would be attached. Victims were nailed to the cross, but often the body would be supported in some form to prevent asphyxiation from hanging and to prolong the suffering. Despite depictions of loincloths in so many paintings, Seneca recorded that victims were crucified naked and sometimes pierced with a stick through their groin to humiliate them and cause pain. A seat in the shape of a horn could be fastened to the stipe, also to torment the victim. Death could take hours or days and could result due to heart failure, shock, pulmonary embolism, or exposure and dehydration.

Women did not escape this cruel punishment. Ida, a Roman freedwoman was crucified by order of Tiberius and Saint Eulalia (c. 290 – 303), was a 13-year-old Roman Christian virgin of Barcelona who was crucified on February 12, 303 AD on the orders of Emperor Diocletian. She was flogged, her breasts were burnt and after the crucifixion, she was decapitated.

At Stake: Anastauro

In pre-Roman Greek texts anastauro usually means to impale. One of the worst prolonged death punishments would be impalement, reserved usually for political adversaries, prisoners of war and in some cases as punishment for a particularly heinous crime. Impalement was usually a public spectacle serving as a determent, humiliation and as a punishment.

Already in the second millennium BC one finds reference to impalement. The Code of Hammurabi (1754 BC) written by the sixth king of ancient Babylon, specified many punishments fitting many crimes. Thus, a woman who murdered her husband for the sake of another man’s love could be punished by impalement – she would have been guilty of adultery too. Several states contemporary to Hammurabi’s reign followed his example. Due to its ideal location on the western bank of the Euphrates River, the ancient city of Mari occupied a coveted place on the trade route between Sumer in the south and the Levant in the west. It was therefore often annexed. Prisoners of war of enemy forces were impaled to deter future invasions, but to no avail, as the city often changed rulership. Captured soldiers were habitually also impaled outside besieged cities to break the morale of the besieged citizens. Records have been found that King Siwe-Palar-huhpak of Elam, (a country east of Babylon), also threatened the allies of his enemies with impalement in a psychological terror campaign and records refer to merchants of Ugarit, expressing their concerns about a colleague who was about to be impaled in Sidon for offending the local deity.

Darius, the King of Persia boasts in the Behistun Inscription: “Then in Babylon I impaled that Nidintu-Bel and the nobles who were with him, I executed 49, this is what I did in Babylon.” It is believed he impaled a total of 3,000 Babylonians. Egyptian kings Merneptah, Sobekhotep II, Akhenaten, Seti, and Ramesses IX also regularly had rivals and enemies impaled and Assyrian King Sennacherib, who became impatient at subjugated kingdoms who refused to pay him taxes, besieged Lachish and impaled the Judean captives. A relief at the palace Khorsabad of Sennacherib’s father Sargon II shows a deviation from the usual impalement method, where the stake was driven into the body immediately under the ribs, as opposed to from inside the anus. This is called the Neo-Assyrian impalement.

The Assyrians were not the only ones to experiment and deviate on the original longitudinal method of impalement, where the stake was thrust from the anus up the body to exit through the breast or neck. Transversal impalement would be from the front torso to the back. A variant of impalement would be to use hooks. ‘Gaunching’ is a method by which the prisoner is first hoisted up and then released onto a bed of hooks or he is hooked through the abdomen, piercing his back, and hoisted onto a horizontal bar, with arms and legs dangling. This method was still in practice during the 18th century by the Dutch to punish runaway or rebellious slaves. Slaves were impaled by the Dutch in Cape Town, South Africa; Suriname (northeast Atlantic coast of America) and Batavia (modern-day Jakarta) during the 17th century. Prisoners were also hung by hooks on the walls of Algiers in the 18th century.

Victims could die within minutes or sometimes their agonizing death could be prolonged for three days, although some records indicate eight days, if the stake missed vital organs and followed the spine. A sharpened oiled stake would accelerate death, while a stumped stake prolonged death as the victim slowly sank down onto the pressure of the stick. Sadistic torturers could keep victims alive by giving them food and water.

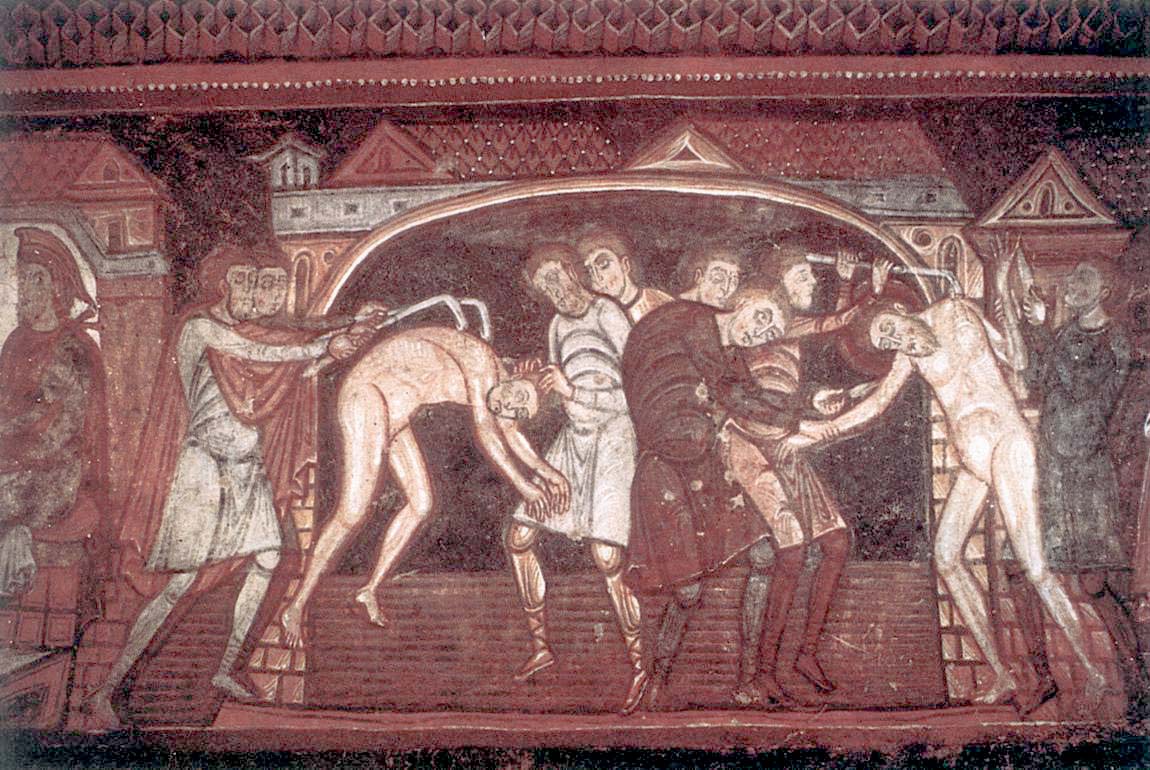

Top image: Sts Savinus and Cyprian are tortured (circa 1100) Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe (Public Domain)