A champion for children’s rights and an activist for socio-economic reform, whose own father was committed to a debtor’s prison, was Victorian era author and literary genius, Charles John Huffam Dickens.

In one of his lesser-known novels, The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens raises the theme of an elderly man, Old Martin, employing an orphaned girl as a companion and nursemaid to take care of him with the understanding that she would receive income from him only as long as Old Martin lives. Old Martin considered that this presented her with an incentive to keep him alive, in contrast to his relatives, who wanted to inherit his money.

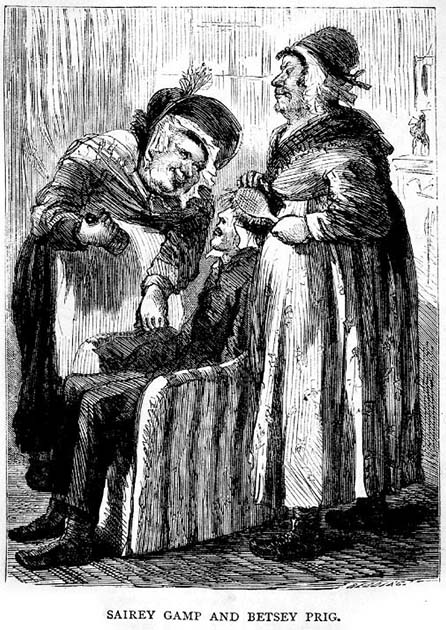

Another character in the novel is Nurse Sarah Gamp (also known as Sairey or Mrs Gamp) an alcoholic who works as a midwife, a monthly nurse and a layer-out of the dead. Even in a house of mourning Nurse Gamp takes advantage of the hospitality of the household with little regard for the person she is there to minister to. Nurse Sarah Gamp personifies the incompetence of untrained nurses of the Victorian era before Florence Nightingale reformed the profession.

In 1847, in unison with his good friend, heiress and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, Dickens founded Urania Cottage in London, a Magdalene asylum or women’s shelter for ‘fallen women of the working class’, which Dickens called a home for homeless women.

Dickens’ novels provided social commentary, critical of the poverty and social stratification of Victorian society and highlighted the oppression and exploitation of the poor.

Almost a century later in 1939, American playwright Joseph Kesselring penned a play titled Arsenic and Old Lace, a farcical black comedy with a plot revolving around the Brewster family, descendants from Mayflower settlers but now composed of homicidal maniacs. The family includes two spinster aunts, Abby and Martha Brewster, who murder lonely old men by poisoning them with a glass of home-made elderberry wine laced with arsenic, strychnine, and “just a pinch” of cyanide.

Against Dickens’ backdrop of workhouses and characters such as Old Martin Chuzzlewit and Nurse Sarah Gamp and almost stepping straight off the stage from Kesselring’s play, three Victorian women make up the cast of my sisterhood of Arsenic and Old Lace.

Jane Toppan

Public Domain

Jolly Jane Toppan was believed to have murdered over 100 people in Massachusetts between 1895 and 1901, of which she confessed to 31.

Jane was a toddler when her mother died of tuberculosis and when she was six, her father dumped her and her middle sister at an orphanage with a dubious reputation. The girls were submitted to abuse in the orphanage. Jane’s eldest sister was committed to an asylum and the middle sister turned to prostitution. At the age of eight, Jane (born Honora) was placed as an indentured servant in the care of Mrs Ann C. Toppan of Lowell, Massachusetts, and Honora became Jane Toppan.

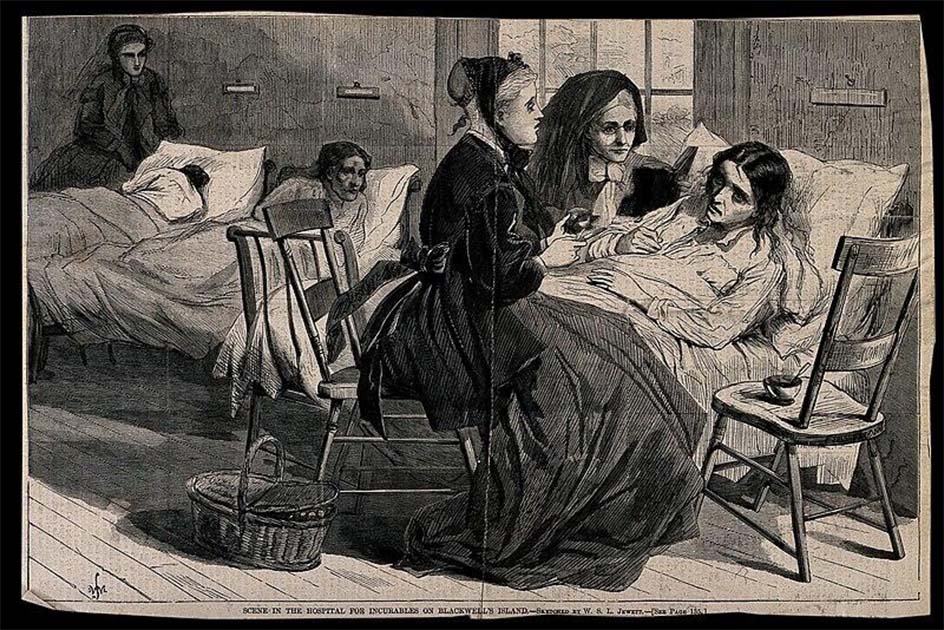

As a training-nurse in 1885 she was given the nickname Jolly, due to her pleasant disposition. Yet her sweet smile was masking a murderous intent. Jane experimented on her vulnerable elderly patients with morphine and atropine, altering their prescribed dosages to see how it affected their nervous systems, and she medicated them to drift in and out of consciousness. When they were unconscious, Jane would get into bed with her patients and she admitted being sexually aroused by killing her patients.

After being fired from the Cambridge and Massachusetts Hospitals for administering opiates recklessly, she became a private nurse. Jane was frequently suspected of petty theft, and soon escalated to murder. In 1895 she killed her landlord, Israel Dunham and his wife. Four years later in 1899 she killed her foster sister Elizabeth Toppan – with whom she had a good relationship as a child – by administering a dose of strychnine. In 1901, after elderly Alden Davis had lost his wife Mattie, Jane was appointed as his live-in nurse. Scarcely two weeks later she killed Alden, his sister Edna, and two of his daughters, Minnie and Genevieve. It later emerged she was the one who had killed his wife, Mattie.

After the massacre, the surviving members of the David family requested a post-mortem toxicology exam on Minnie and it tested positive. On October 29, 1901 Jane was arrested for murder. By 1902, she had confessed to 31 murders.

In her trial Jane professed her sanity, claiming she knew what she was doing was wrong, in the hope that she would one day be released. However, the jury found her insane and she was committed to an asylum, typically exemplifying the Victorian mentality that female criminality and deviant sexuality can only be ascribed to insanity or feeblemindedness. She died in the asylum at the age of 84.

Amelia Dyer

Growing up in the mid-19th century in a small village called Pyle March just east of Bristol in Britain, Amelia Dyer (neé Hobley) was the youngest of five siblings. She had lost two sisters in their infancy and her father was a cobbler. As a child Ameilia developed a love for literature and poetry. Perhaps this gave her some reprieve, for up to the age of ten years, she had to care for her mother who suffered from mental illness caused by typhus and often witnessed her violent outbursts. After her mother’s death, she was passed on to relatives to be raised. Her father died in 1859.

At the age of 24 her life changed when she moved into lodgings in Trinity Street, Bristol, where she met and married 59-year-old George Thomas. The marriage afforded her the opportunity to train as a nurse. Amelia and George were married for eight years and produced one daughter, but in 1869 George passed on. Amelia needed an income.

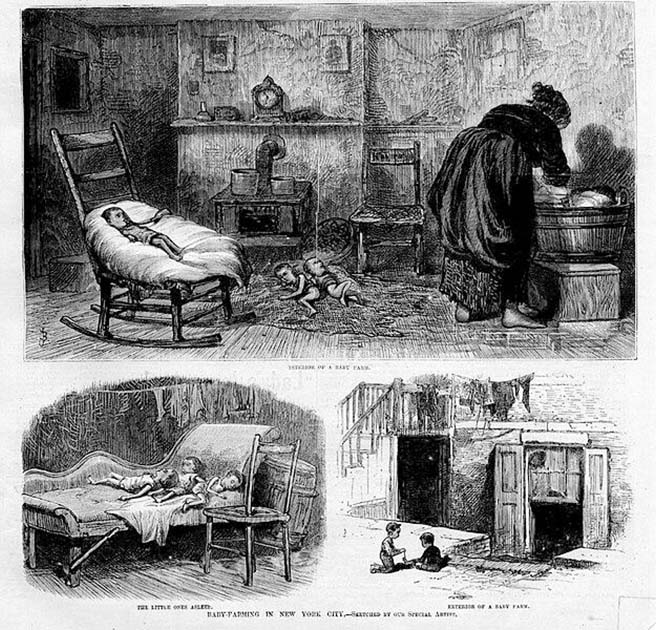

Amelia soon figured out she could earn much more money if she rented out lodgings to unwed mothers and take custody or arrange adoptions for the babies – known as the Victorian practice of baby farming.

The 1834-Poor Law Amendment Act had removed any financial obligation from the fathers of illegitimate children, and only allowed for impoverished, unwed mothers to receive donations of food, money, or clothing from the parish, if they went to live in the workhouse. This forced the mothers to pay baby-farmers a once-off amount or weekly fees to become custodians of their children. Some children were unwanted, but many mothers had the intention of collecting their children once their circumstances improved.

Social class distinction determined the price of such an arrangement. Wealthy families wanting to cover up the scandal paid up to 80 pounds, while a father needing to hide his involvement could be extorted out of 50 pounds, but mostly impoverished single moms paid five to ten pounds. Charles Dickens was aware that many Victorian baby farmers exploited this business plan and turned into Angels of Death. His character Oliver Twist was subjected to baby farming, and then to an orphanage, highlighting the plight of these children.

In order to be trusted as the custodian for babies, Amelia had to be seen to be respectable, so in 1872 she married William Dyer, a brewer’s labourer from Bristol and she had two children with him, before finally abandoning him.

Amelia soon found the babies in her custody troublesome and realized she could turn a profit if she simply allowed them to starve to death, or to murder them shortly after pocketing the once-off fee. For a while she went undetected until a doctor who had to sign the death certificates for many babies dying in her care, raised suspicion and remarkably Amelia in her first brush with the law, was only sentenced to six-month hard labour for the death of an infant in her establishment.

Upon her release, she resumed her baby farming practice. Whenever she found herself in hot water, she admitted herself to asylums – having learnt all about symptoms when she tended to her mother as a child. Godfrey’s Cordial, known colloquially as “Mother’s Friend” – was a syrup containing opium that baby farmers administered to babies to suppress their hunger and to keep them constantly sedated. Amelia had become addicted to alcohol and opium, which could have caused serious mental problems.

Weary of doctors who had to sign death certificates, Amelia decided to dispose of the bodies herself. Parents wanting to reclaim their children raised suspicion when they disappeared and whenever Amelia drew the attention of the police, she relocated to another town and set up shop again using an alias until she finally ended up in Reading, Oxford.

In January 1896, she accepted a baby girl, called Doris Marmon for a fee of ten pounds and travelled to her daughter’s home in London where she strangled the baby girl with white dressmakers’ tape. Then she accepted a baby boy and removed the tape from the neck of the baby girl to strangle the boy. She later confessed to enjoy watching the babies die in such a manner. Amelia returned to Reading in Oxford with the bodies of the two babies in a carpet bag and dumped them in the River Thames.

Unbeknown to Amelia in March 1896, the police had retrieved another bag with a dead baby from the Thames. Painstakingly Detective Constable Anderson used microscopic analysis of the wrapping paper inside this bag and deciphered a faintly legible name, Mrs. Thomas, and an address. The police kept Amelia’s home under surveillance and then they used a young woman as a decoy. Amelia knew her ticket was up when the police raided her home, which stank of human decomposition. Although no bodies were found, there was enough evidence in the form of adoption papers, receipts, letters and the white dressmakers’ tape for them to arrest her. Tracing her steps back it was estimated that she may have killed over 400 babies. When the Thames was dredged, six more bodies including the last two victims were discovered, all of whom were strangled with the dressmakers’ tape.

On 22 May 1896, Amelia Dyer appeared at the Old Bailey and pleaded guilty only to the murder of Doris Marmon – her defence was insanity. Amelia was hanged at Newgate Prison on Wednesday, 10 June 1896.

Amy Archer Gilligan

Across the Atlantic, Amy Archer Gilligan’s sweet granny smile masked an Angel of Death, who murdered many residents in her nursing home called the “Archer Home for the Elderly and Infirm”. Amy and her first husband James Archer had brought the property on Prospect Street in Windsor Center, Connecticut in 1907 with their savings. Three years later James died of a kidney disease and Amy benefited from an insurance policy she had taken out on his life a year prior. It enabled her to keep the nursing home, promising life care for her ailing tenants. However running costs were expensive.

Luckily for Amy in 1913, Michael Gilligan, a wealthy man, took an interest in Amy and he wanted to invest in her home. Unlucky for Michael, after three months of marital bliss, he died on February 20, 1914. Despite him having four adult sons, Amy was the sole beneficiary of his will. It later turned that Amy had forged the will.

Between 1907 and 1917, a total of 60 deaths were recorded at Amy’s establishment. Amy’s clients showed a pattern of dying not long after ceding a large sum of money to her. One of them, Franklin R. Andrews, was very healthy on the morning of 29 May 1914, but very dead that evening. His family raised the alarm with the district attorney, who dismissed it.

Andrew’s sister Nellie Pierce then took her suspicions to the press, who by May 1916 began a series of articles called Murder Factory. This caught the attention of the police, who took a year to conclude their investigation. Exhumations of five of the bodies revealed either arsenic or strychnine poisoning. Deviously Amy dispatched her residents to buy poison for rats, unbeknown to them that they would be killed by the very same poison they had purchased. Amy personified the fictional characters of Abby and Martha Brewster in the play Arsenic and Old Lace.

Amy was arrested and charged with five counts of murder. Charges were dropped for all but one – the murder of Franklin Andrews. She was found guilty and sentenced to death but pleaded insanity on appeal. This time she was sentenced to life and she died in Connecticut Hospital for the Insane in 1962. There was no justice for the other residents who died at her nursing home.

There are parallels between the childhoods of Jane Toppan and Amelia Dyer; both had sick and unstable mothers; both their fathers abandoned them to foster care, either in an orphanage or to family members; both came from large, impoverished families – they were neglected children. This they have in common with male serial killers – they were not all abused, but they were all neglected. Not much is known from the childhood of Amy Gilligan except that she was the eighth of ten children. All three became nurses, a profession providing them legitimate access to victims.

Female serial killers differ from male serial killers in the sense that female serial killers are usually acquainted with or related to their victims and they have free access to them. Male serial killers usually randomly select strangers who fit into their idiosyncratic victim profile. Male serial killers are not known to kill babies, as preferred victim preferences.

I have warned so often that serial killers are normal people, they are not spawned by aliens they have parents. They could be your neighbours, brothers, fathers, sisters, grandmothers or the little old lady who lives down the lane.

Top image: Two Old Ones Eating Soup by Francisco Goya (1820–1823) (Public Domain)