In October 2002, Soweto, a township designated predominantly for Black people during the Apartheid era, located south-west of Johannesburg, South Africa, was rocked as a volley of bombs exploded, one-by-one over several hours, killing a woman.

A month before the explosions on 16 September 2002, Detective Superintendent Tollie Vreugdenburg, former Commander of the Bushveld Murder and Robbery Unit, and by then the Area Deputy Head of Detectives, was sitting at his desk, contemplating early retirement when he received a call about some strange activities on a farm in his district. Not much information was relayed, except that Crime Intelligence was involved. He decided not to delegate the call-out, but rather to visit the scene himself, as he was bored “pushing papers around.” He was also acquainted with the owner of the farm. Besides ammunition, he did not find much on that particular farm – farmers legally armed themselves due to the spate of farm murders and Vreugdenburg had investigated many of these while he was still Commander of Murder and Robbery. He left the farm, but his detective intuition led him to stop at a neighbouring farm, where he knew one of the close friends of the farmer lived. The friend’s answers to Vreugdenburg’s questions were vague and he warned him that he would have to come clean if they were involved in something sinister. Two days later the man contacted him and spilled the beans. They were part of a group of right-wing extremists, called the Boeremag, who planned to overthrow the state, by detonating many bombs.

The wheels of the state spun furiously for a change and within a few days, Vreugdenburg was relieved of his office job and appointed lead investigator in the case. It turns out that his life was miraculously interwoven with many of the later suspects.

Three months later on 11 December 2002, after months of covert infiltration, in a scene reminiscent of an action movie, Vreugdenburg and his team descended by helicopter on a farm and uncovered a cache of arms including one-and-a-half tons of explosives. By then Vreugdenburg and his team had arrested 23 men. The last arrests literally happened within two days before four bombs of 300 kg of explosives each were detonated all over the country.

The trial commenced in May 2003 and turned out to be the longest in the history of South Africa for it lasted until 2013. It effectively took Superintendent Vreugdenburg out of active duty for a decade, ruining his plans for early retirement.

By 2011, rookie journalist Karen Mitchell was tasked to report on the trial. This is her story:

I remember glancing across the front pages of newspapers just as I started High School and seeing the word “Boeremag” and something about how they were planning to plant bombs across South Africa. At the time, these articles meant little to nothing to me. I was just glad that “the bad guys” had been caught.

Fast forward to about nine years later – 2011 – when I was deployed to cover the trial as a young, intern journalist, where that vague memory informed my understanding of the trial the night before I had to go to court. Of course, I ended up spending that entire night reading up on the case that was to become the longest-running trial in the country’s history, spanning a decade. When I arrived at court the next day, I knew the names of the 23 accused men, their backgrounds, and that they had been awaiting trial prisoners since the early 2000s. They were ordinary men, mostly educated, not the kind one would have expected to be involved in such violent terror acts.

The background to the trial was that they had planned to overthrow the ANC government to return power in the country to the Boer (translating to ‘farmer’ – but the term Boer stretches into the identity of a particular White, Afrikaans speaking demographic) population. Not the whole White population, per sé, but a country in which the Boer nation could live out their ideals and values – and be in control of their own sovereignty. That was the gist of it. Or so I naïvely thought.

Through a strange twist of fate, I secured an interview with one of the accused in prison in 2011 and for the next few years until 2017, a human saga unfolded. Already during my first visit to him at the Kgosi Mampuru Correctional Facility in Pretoria, realised I had to document the full story for people to comprehend the complicated nuances of the case. I had to write a book to delve into the various layers of the Boeremag story.

No matter how much research I conducted over however many years, I was never able to find an article that covered the full narrative. Almost every article I came across referred to the Boeremag as either “right-wing,” “racist,” or as “coup plotters.” And so, I started to piece together the different versions of events from witnesses’ testimonies, interviewing authorities, and reviewed the case archives that took up an entire room in the basement of the Palace of Justice in Pretoria.

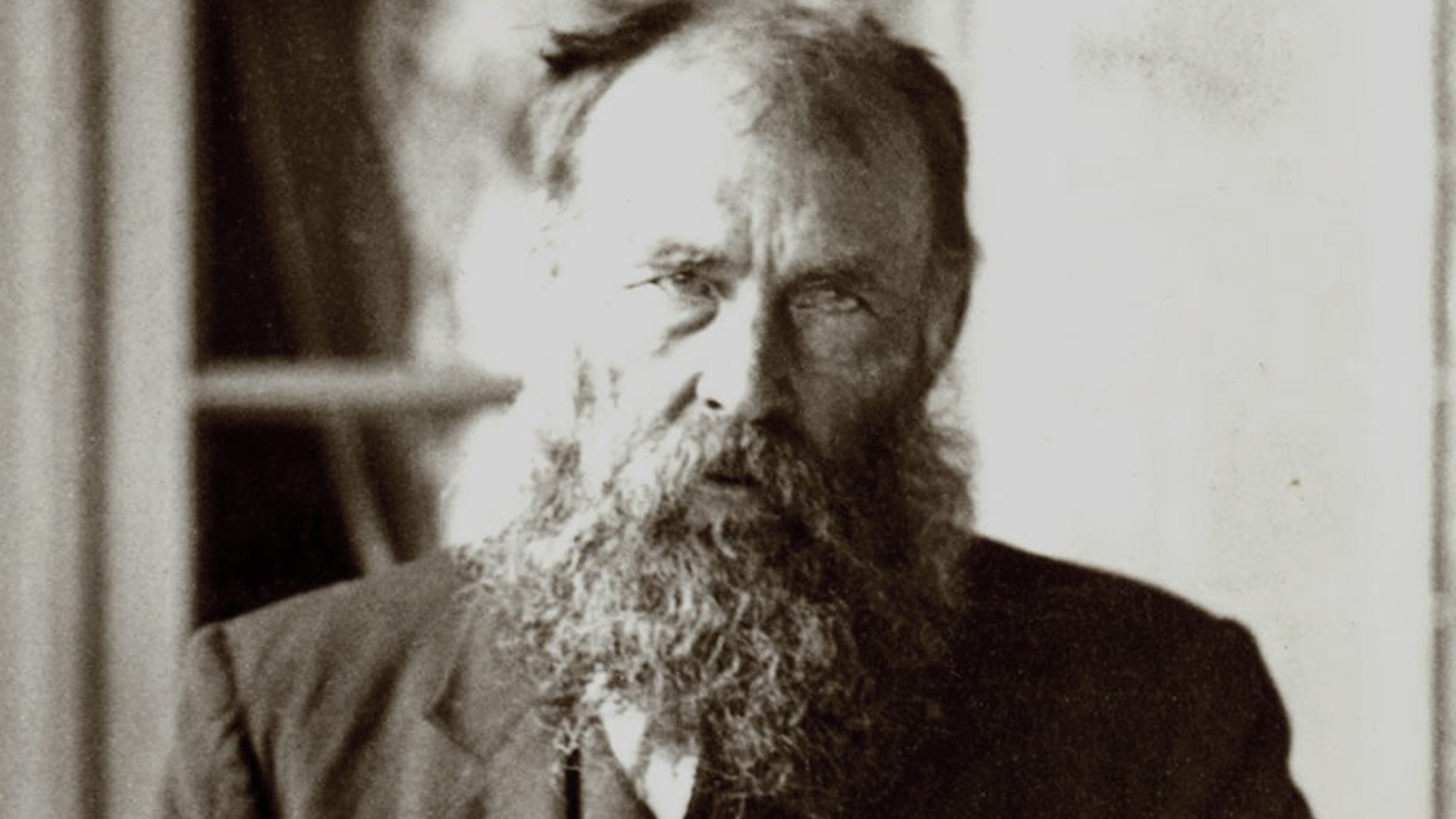

There had been countless references to Siener van Rensburg during the trial – Siener was a late 19th to early 20th century prophet who would be best described as the South African Nostradamus in layman’s terms. When the Boeremag first assembled to discuss their plans on how to govern the country, Siener’s visions played a pivotal role. His visions were heavily relied upon in his own lifetime, during the South African War from 1899-1902, since his predictions about where the enemy would be, were often accurate. However, like other prophets, his visions contained symbolism and references which meant they could be interpreted in various ways – mostly by means of one’s own perspective, coloured by personal experience and scope of knowledge.

The Boeremag were convinced that Siener’s visions about “The Night of the Long Knives” indicated that there would be a black-on-White onslaught in the country, particularly after the death of an influential black leader. However, the group of individuals at the helm of the organization decided that they were not going to wait for The Night of the Long Knives to arrive. They were going to be pro-active by triggering it themselves through anarchy. It is also for this reason that they later orchestrated an attempt on former President Nelson Mandela’s life, which failed.

Much like the French Revolution was born from the discourse of French lawyers and philosophers such as Maximilien Robespierre in Parisian coffee shops in 1789, the organization of the Boeremag was founded in a similar informal manner by a few individuals who talked about the current state of the country in the early 2000s, and how they were concerned about the country’s future. These individuals shared overlapping values and right-wing leaning ideals. They initiated contact with more individuals whom they knew shared some of the same ideals, roping them in to attend meetings where they would talk about their perceived scenarios that could soon face the country. The timing coincided with the troubles in neighbouring Zimbabwe, where the currency had collapsed after mass land reform. The initial leaders of the Boeremag spoke about these troubles in their meetings and linked Siener’s visions to the situation.

It is important to note that there were different leaders of the Boeremag during different stages. For instance, in the beginning, they were preparing to trigger The Night of the Long Knives by occupying military bases. The second leader expanded the existing plan and suggested the organization should plant various bombs across the country. Under the third leader, the plan developed even further. By this stage, they planned to plant bombs in strategic areas which would undoubtedly have led to mass bloodshed considering just how much explosives they had manufactured. But only a few of the people in the upper echelons of the organisation were in the know about the full extent of the plans. For example, newcomers to meetings were not aware that the Boeremag planned to detonate bombs. They were told that it was a defensive plan (which it clearly was not) and that they needed to start stockpiling supplies and prepare to protect themselves.

One needs to ask why people in a democratic South Africa were drawn to these meetings? Putting the trial into context, those who participated were not necessarily all Afrikaners or Boere. Some of the participants were certainly Boere, who held conservative and nationalistic views. These were individuals who clung to the past – to an era when they were regarded as being superior based on the colour of their skin during the Apartheid reign. The others, who did not regard themselves as Boere, obviously found some thread of resonance with the message.

Such as those who believed in the Israel Vision. In the early stages of the Boeremag, they realised that it was incredibly easy to recruit members who believed in the Israel Vision. Those who follow this belief system consider themselves as being part of God’s chosen people because they believe they are direct descendants of the lost tribes of Israel. They believe they are superior and that it is their duty to spread God’s message so that they will be saved when the Reckoning comes. This somewhat “underground” movement also believes in racial segregation – mainly because God had ordered that Israel stay away from its neighbours to avoid being influenced by other religious practices. In short, they have deep-rooted values that make them feel superior and intolerant of “the other.”

My conviction is that the men who got involved needed to establish an identity for themselves in a country that had seen so many different eras with so many different challenges and conflicts. Eras in which many White and Afrikaans men would have lost their lives while fighting for their country. There was a deep-rooted ethos of discipline, honouring your country, heritage, pride in ownership of land (while, ironically, the Black population was not allowed to own land since the 1913 Natives Land Act had kicked in). These men had generational experiences of being in some sort of militant role to protect and defend what was theirs.

When the first conversations started rumbling in the late 1990s that would later lead to the formation of the Boeremag, South Africa’s democracy was still in its infancy. For some of the White and Afrikaans-speaking population there was uncertainty, there was bitterness, and there was change. But there was also fear. A fear of the unknown. A fear of wondering what would happen to the young generations and those to follow if they were to be governed by the ANC – a political party that had been considered terrorists just a few years prior.

This fear could easily have been the catalyst that would unite the Boer and Afrikaans populations. They could have agreed on certain aspects while disagreeing on others – but if they found resonance around discussions of White people having to protect themselves in the country against the “other” and the dangers of the unknown, one can see how the Boeremag may have gained some traction.

Some of the Boeremag members did not share the same political, religious, or cultural views. These individuals were not the same in bone and marrow. They had different reasons for joining the Boeremag and, most likely, different visions of what the future of South Africa should hold. Eventually they could not succeed in unifying their different ideals to create the mighty organization they had envisioned. The slightest disagreements would dissuade individuals from participating, until only those with staunch values remained.

In the Boeremag organization’s context, they were preparing to defend and protect – something that had been engrained in their psyche over several generations. However, the members of the Boeremag who were arrested for treason did not defend and protect. They planned their attacks over years. Members had to swear an oath of allegiance, under the threat of death, if they were to say anything. They did not care about the en-mass bloodshed that would have ensued had they not been stopped, by Superintendent Vreugdenburg and his team. Their values convinced them they were superior. By what psychological means did these ordinary men proceed to become so callous?

Despite their heinous actions, I got acquainted with several of the men during the course of the trial. They were fathers and husbands, and their families were paying the price for what they had been accused of. I have never excused the Boeremag’s actions, and I have always told the story of what the South African judiciary found to be the truth. By speaking to the men for so many years, getting to know some of their children and their families, I realised that many, many people were suffering.

I have often wondered: “Was it worth it?” And, of course, it was not. But their beliefs and ideals drove them past the point of reality and to commit morally irreprehensible deeds. While the rest of the country was working on nation building – this group was planning to plant bombs and to create a country in which they alone could feel comfortable to live in. They did not become high treasonists overnight.

After being awarded the Silver Cross for Bravery twice, Superintendent Tollie Vreugdenburg finally retired in 2022 and is now a consultant in counter terrorism to various African countries. Karin Mitchell wrote her book. Penguin Random House will be publishing Karin book, about the Boeremag in 2025.

Top image: Nicolaas Pieter Johannes Janse van Rensburg, alias Siener van Rensburg, South African prophet (CC BY-SA 4.0)