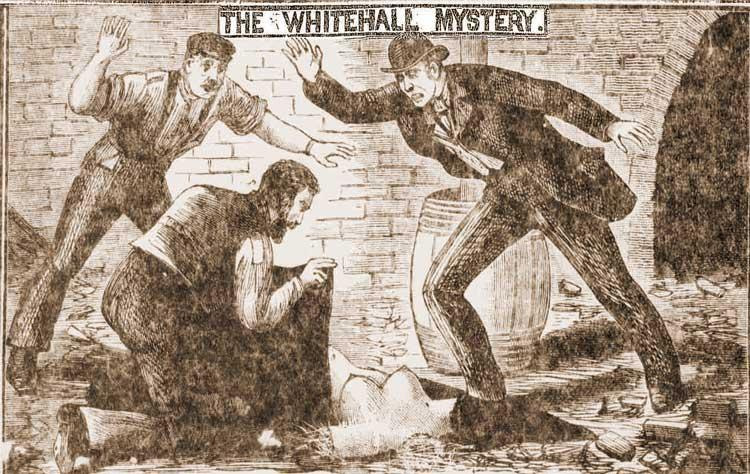

The sensational reporting of Jack the Ripper terrorising Whitechapel London in the late 19th century, can serve as an archetypical portrayal of the dichotomous troubling relationship between the press and serial killers. The public craved all the details of the murders of the prostitutes and the press complied with gory descriptions, accompanied by a sketch of the crime scene of an eviscerated Catherine Eddows and an official police photograph of the mutilated body of Mary Jane Kelly in graphic detail, while Jack was depicted as a mysterious hooded and cloaked, almost gentlemanly, figure with a top hat.

Almost one and a half centuries later, the media still amplifies serial killers’ notoriety, turning them into mythic figures, almost comic book superheroes or supervillains, feeding a dark cult-like adulation. An explosion of social media in the 21st century has turned into a media circus as clowns enter the arena, turning serial killers like Ted Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, and many others into cultural icons, dramatizing their crimes to feed the frenzy with macabre depictions, dripping with fake blood splatter.

On a real-life crime scene, there are no “special effects” as in the movies, tv-series, YouTube or TikTok videos. On a real crime scene there is no actor playing the ‘dead body’ who gets up after the director calls “CUT”, washes off the stage make-up and goes out for a beer. Real crime scenes are messy and an onslaught on one’s senses and soul and causes post-traumatic stress – it impacts even hardened detectives.

I acknowledge an academic approach in the interest of research and education, or even lay people’s natural fascination with serial killers and true crime, for since the dawn of humankind people have a need to understand that which they fear. Unfortunately an escalation to an almost blood-thirsty craving for the macabre, has led to the commodification of the killers’ stories, merchandising and creating “killer brands”. Some killers, like Charles Manson, have become pop culture icons, with their images emblazoned on T-shirts and memorabilia. This commercialization feeds into the myth of the serial killer as an iconic figure, creating a gaping chasm between the synthetic sensationalism and the reality of their crimes and the suffering of their victims and their families.

One mastermind at exploiting the public’s interest and feeding their frenzy, with the help of the media, is Stephane Bourgoin, the so-called French author and ‘serial killer expert’ who excelled at capitalizing and profiting from this synthetic sensationalism. Stephane went so far as to claim that his wife was brutally murdered by a serial killer and indulged audiences and reporters in the most horrendous details of such a murder, while the next moment he shares a joke with a reporter on whether crime scenes made him nauseous or not. He promised his fans if they bought his books he would mail them parts of a serial killer, whose body he allegedly possessed. He wore merchandized serial killer T-shirts

I knew him personally and amongst others he also stole my book and tried to impersonate me. For his full story please watch the National Geographic and The New Yorker Studios documentary “KillerLies: Chasing A True Crime Con Man,” which premiered on Wednesday, August 28th, on National Geographic, with streaming on Hulu.

There is a difference between an expert and an aficionado. In court an expert witness is deemed a person who has an appropriate academic qualification, usually a doctorate’s degree, who has conducted research on the topic and has acquired years of personal expertise in the field they are testifying on. A judge respects an expert’s opinion which is there to guide the judge and enlighten them on topics.

Reading many books and watching many YouTube or TikTok videos on serial killers, watching tv documentaries or fictional shows about them, and copying other people’s books does not make one an expert, it may make one an aficionado. I can appreciate the enthusiasm and passion of an aficionado, but at least acknowledge the limitations of the ‘expertise level’ as amateur.

Many aficionados can only quote statistics and demographics, reciting the names, dates and number of victims of the killers, like a schoolboy who collects baseball cards, to recite the names, dates and scores of baseball players. The internet crawls with informative websites, and often their facts are just plain wrong.

But Stephane Bourgoin went further by piggybacking on other real experts’ experiences, claiming them to be his own, impersonating a profiler or a detective. His masquerade was so convincing he became a celebrity, even presenting lectures at academies such Ecole National de la Magistrature and the Centre National de Formation de la Police Judiciare, without any official training and by claiming that he was trained by the FBI – which was a lie.

Repeating a previous pattern, Stephane came to South Africa and had permission to shoot a tv documentary, which was often granted to international production companies. Under the blanket of the VM production company, it was arranged for Stephane by the detectives just to meet two South African serial killers unofficially– Velaphi Ndlandlamandla and Steward Wilken briefly. These were not formal interviews and he would hardly have had enough time to ask them in-depth questions – it turned out basically as short photo sessions. During the mid-1990’s, there was no social media, no Instagram and no-one, certainly not myself nor the detectives, had any inkling that he would later use these photos as so-called proof that he had interviewed or interrogated South African serial killers or that he would use this for his personal benefit and profit and that they would eventually become a part of his so-called ‘repertoire’ of serial killer interviews. He certainly milked those informal photo sessions for personal profit.

Had any French journalist done due diligence and checked Stephane’s passport, they would have realised he was not in South Africa on the dates he claimed to have participated in investigations. The South African Police Service would never allow a civilian, let alone a member of the press, to attend a real crime scene or interrogate a suspect, as it will compromise the investigation and eventual trial.

While the media’s role in disseminating information is crucial, it can also significantly hinder criminal investigations. The rush to break a scoop often leads to the premature release of sensitive information, alerting suspects, jeopardizing evidence, interfering with witnesses and complicating investigative processes.

Reporting on the exact location, or specific details of a crime scene can compromise the pointing out of a crime scene. Some witnesses or victims’ family members sell their stories to the media before the trial. Especially in cases of remote crime scenes, the often-intimate knowledge only the killer would have, indicates culpability. If it is reported in the press before the trial, his defence could claim in court that he was tortured during interrogation and confessed to what he had read in a newspaper under duress. During the Station Strangler investigation, the whole community, under supervision of the police, combed the dunes of Mitchells Plain for bodies. Norman Simons pointed out the correct crime scenes, even one that went undetected, but if he was charged on these cases, his defence could have argued that just about everybody in that community knew where most of those scenes were. He was convicted only on one case and an inquest on the others found that he was probably responsible. This full documentary is to be released on Showmax in September 2024.

Any police department has a moral duty to warn the public if a serial killer is on the loose, so they can take precautions. Most of the members of the public, however do not, and think it can never happen to them, or that a person is much too ordinary to be a serial killer, exactly because they have been led to believe that serial killers are idolized or sleazy comic book monsters, with crazed eyes, foaming at the mouth. They are not. They are ordinary people.

Media portrayals can also distort public perceptions of law enforcement. Sensationalized reporting often casts investigators as either incompetent or corrupt, focusing on perceived failures while neglecting the complexities of criminal investigations. This can erode public trust, making it more difficult for the police to secure cooperation and carry out their duties effectively. Conversely, glamorizing law enforcement can create unrealistic expectations regarding how quickly and easily cases should be solved. Only in the movies are arrests made and cases solved within the 45-minute span of an episode. The media seldom reports on the drudgery, late nights, groundwork, observations, blunders and frustrations of real investigations – that is just not entertainment.

One of the most significant dangers of sensationalist media coverage is the creation of false narratives that can undermine justice. Serial killer cases often involve complex psychological profiles, and forensic evidence that are difficult to convey accurately in a news story. When the media simplifies or distorts these elements, misunderstandings arise that confuse the public. Some people in Mitchells Plain still believe Norman Simons was not the Station Strangler, due to false reports. The same applies to David Selepe, who was shot while trying to escape when pointing out a crime scene. Since his trial never realized, conclusive evidence pertaining to his involvement was never made public.

The media’s role in shaping serial killer legends is undeniable, but it comes with significant ethical and societal implications. By idolizing and sensationalizing these figures, the media can distort public understanding, glorify criminals, and compromise justice and even worse, demean victims and their families. As the demand for true crime content continues to grow, it is crucial for formal media outlets, and informal outlets such as YouTube, TikTok and Websites to present such stories with responsibility, accuracy, and respect for the victims, ensuring that the pursuit of public interest does not come at the cost of truth and justice. Does the public not also have a responsibility to check the credentials of those reporting on True Crime?

Top image: “The Whitehall Mystery” of October 1888 Illustrated Police News (Public Domain)