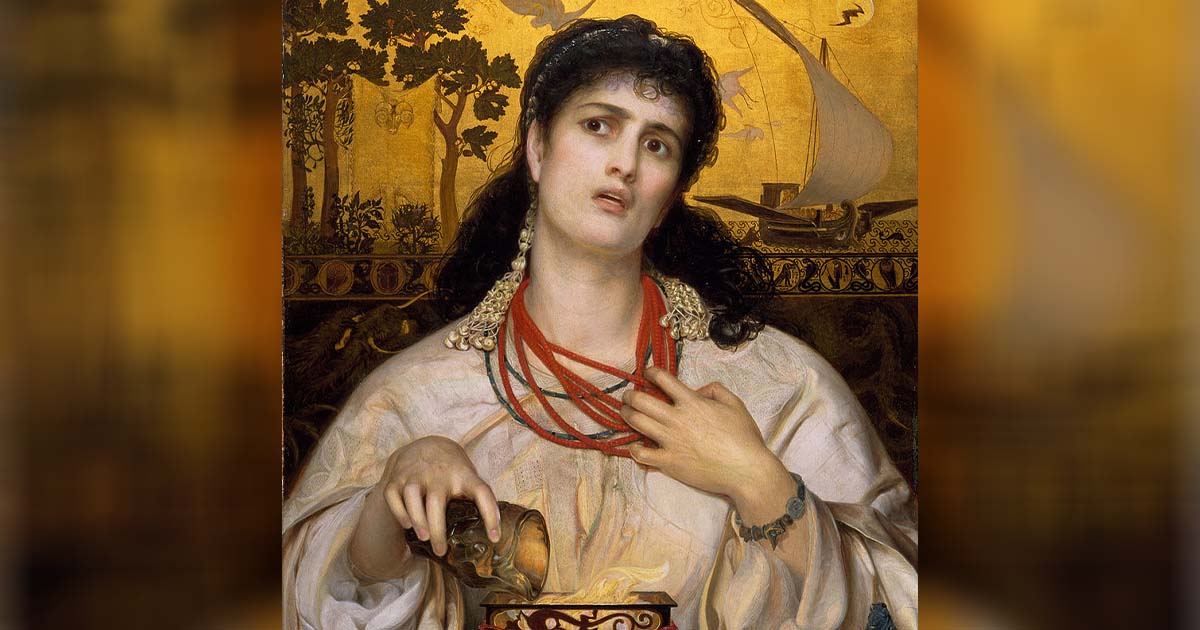

In Greek mythology, Medea, princess of Colchis, was regarded as a sorceress, an accomplished “pharmakeía” and is often depicted as a high-priestess of the goddess, Hecate. When Medea was abandoned by her husband Jason in favour of Glauke, princess of Corinth, she took revenge on her rival by sending her a dress and a crown dowsed in poison, killing not only Glauke but also her father King Creon, who tried to save his daughter.

Poison has always been an option for those afflicted by love, hate, ambition, jealousy, and revenge, to manipulate circumstances in their favour. Since it was difficult to trace, tasteless and almost impossible to prove, poisoning became the go-to-easy-fix in Renaissance Europe to rid oneself of political or love rivals. In the backstreets of Paris, it was readily available and sold over the counter at apothecaries. “What’s your poison?” had a literal meaning, as ladies displayed little vials of poison on their dressing room tables, for poison was also used as cosmetics.

During the Renaissance fortune tellers, con-artists and so-called alchemists and apothecaries cashed in on the gullibility and superstitions of their customers, selling them potent love potions, whether they were royalty or commoners. But when it came to the darker arts and purchasing lethal poison to murder, mere humans lacking courage for meddling in life-and-death-matters, needed the back-up of external, dark forces, which led to Black Masses. Abortions and infanticide provided a constant supply of baby sacrifices required for the Black Masses.

Thus, a sinister syndicate of fortune tellers, con-artists, diviners, purveyors of poisons and love potions, corrupted clergy, servants and sorcerers operated in the shadowy underworld in Paris, visited by those of the upper echelons, who arrived in unmarked carriages, hiding behind their hooded cloaks, overconfident in their aristocratic birthright that they would never be exposed. However, scarcely a decade after the Spana Prosecution in Italy, a similar scandal of the Affair of the Poisons rocked and shocked the court of King Louis XIV the Sun King of France, between 1677 and 1682.

Marie-Madeleine d’Aubray was loved and spoilt by her father, Antoine Dreux d’Aubray who was immensely rich, but being a daughter, she was not in line to inherit his fortunes. This would befall her brothers.

Upon her marriage her father promised to bestow a dowry of 200,000 livres on her. At 21, she married Antoine Gobelin, Baron de Nourar, who later became Marquis de Brinvilliers, whose estate was worth 800,000 livres. Supplemented by her dowry, Marie-Madeleine had no need for money, but she had other needs.

Known for entertaining several paramours during her marriage, she began a serious affair with Captain Godin de Sainte-Croix, a colleague of her husband. Since Marie-Madeleine was not discreet her father decided he had to intervene for a stain on her reputation would damage his standing. Marie-Madeleine was also separating her wealth from her husband’s due to his excessive gambling, but this was akin to a divorce – much frowned upon in her aristocratic society. Her father had Captain de Sainte-Croix arrested and committed to the Bastille where he met the infamous Exili, who was an expert on poisons.

Upon his release from prison, Captain de Sainte-Croix decided to put his newly gained knowledge to use and founded an alchemy business, legally obtaining the necessary license to distil his poisons. It was not long before Marie-Madeleine visited him and under his guidance began experimenting with poisons on patients in a hospital and she developed homicidal ideation about killing her father. Marie-Madeleine later admitted if her father had not arrested Captain de Sainte-Croix, she may never have poisoned him.

In 1666 Marie-Madeleine employed a man in her father’s household who gradually began poisoning him. She was at her father’s bedside when he finally died that September. As expected she inherited some money, and it took her a few years to spend it. Four years later she targeted her brothers, using the same modus operandi of planting an employee in their household to poison them. The bothers were both dead by September 1670. In all cases, the deaths seemed due to natural causes – the suspicions regarding her brothers’ sudden deaths came to naught.

Marie-Madeleine went undetected until Captain de Sainte-Croix’s death in 1672, when her letters and incriminating evidence were discovered among his personal effects. Marie-Madeleine fled to England, but her accomplices were tortured and executed. In 1676 she was eventually traced to Belgium, arrested and repatriated to France. She was imprisoned in the Conciergerie, and initially denied all knowledge of her crimes. She was to be tortured before finally being executed by beheading and then having her body burned as a public spectacle at the Place de Greve in Paris, with many aristocrats in attendance. Thus, paranoia was ignited among the aristocrats that their birthright no longer protected them, and it took fire in the halls of Versailles, the court of King Louis XIV, Sun King of France.

Long suspecting there were more poisoners in his realm and perhaps in his court, by April 1679 King Louis XIV appointed special commissioners and a special court at the Chambre Ardente, to conduct investigations and prosecute the poisoners. Chief of Police, Nicolas de la Reynie, one of the commissioners was the chief investigator and he began rounding up fortune tellers and alchemists, and soon discovered a chief antagonist in this saga was Catherine Montvoisin, called La Voisin, who reminiscent of ancient Rome’s Locusta, dispensed the “inheritance powders” as poisons were referred to.

La Voisin and Marie Bosse, another key player in the poison-for-sale network, played ping-pong in incriminating each other, much to De la Reynie’s advantage, who finally had them confronting each other face to face. Typical when faced with the consequences of a crime, a survival instinct kicks in and the perpetrators would sell each other out, implicate and make false accusations, especially under torture – anything to avoid excruciating death such as being burnt alive. This complicated the work of those appointed to investigate as well as those appointed to judge, but torture was regarded as a legitimate way of securing a confession, especially when there was no scientific proof.

Marie Bosse was burnt alive at the Place de Greve but La Voisin was spared for De la Reynie was convinced she had more secrets to reveal. And she did. She implicated Olympia Mancini, the Countess of Soisson; her sister, the Duchess of Bouillon and François Henri de Montmorency, Duke of Luxembourg amongst others. Eventually La Voisin was burnt alive, but her daughter Marguerite Monvoisin was still imprisoned.

Olympia Mancini, the Countess of Soisson

Olympia Mancini was the niece of King Louis XIV’s chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin. A native Italian, she was born and raised in Rome, her father being Baron Lorenzo Mancini, an Italian aristocrat who was also a necromancer and astrologer. After his death her mother brought 12-year-old Olympia and her sisters to Paris, for their uncle Cardinal Mazarin to secure them husbands. Olympia was married on 24 February 1657 to Prince Eugène-Maurice of Savoy, Count of Soissons and she borne him eight children.

Olympia was appointed Superintendent of the Queen’s Household which gave her authority over all the ladies at Court with the exception of the Princesses of The Blood. She had been a mistress of the King for a brief interlude, and she enjoyed his trust, until he favoured Louise de La Vallière. According to La Voisin, Olympia plotted to poison Louise de La Vallière, her husband, three servants, as well as the King’s aunt Henrietta of England. In January 1680, Olympia fled the royal court to Brussels, thereby avoiding arrest and being put to trial for involvement in the Affaire des Poisons. Then she settled in Spain, where 1690 she was suspected of having poisoned Queen Maria Luisa of Spain, the daughter of Henriette and niece of Louis XIV. She was ordered to leave Spain and returned to Brussels, where she died in 1708. She was never prosecuted.

Françoise-Athénaïs, Madame de Montespan

At the age of 25, Françoise-Athénaïs, Marquise de Montespan supplanted Louise de La Vallière in the King’s affections. Madame de Montespan had seven children by the King, six of them were later legitimised but only four survived infancy. The children were raised by Madame Scarron, also known as the Marquise de Maintenon.

Then in 1679 the King’s eye fell upon Marie Angélique, Duchess of Fontange. Marie Angélique was said to be “as stupid as a basket.” The Duchess of Orleans wrote “she is a stupid little creature, but she has a very good heart“. When Marie Angelique fell pregnant by the King, Madame de Montespan no longer considered her to be a passing fancy.

After two miscarriages, the King grew tired of Marie Angelique and she was sent to the Abbey of Port-Royal, where she contracted a fever and gave birth to a still-born baby daughter. She died on 28 June 1661, not yet 20 years old. Since she died during the Affair of the Poisons, it was suspected that she had been poisoned.

La Voisin never admitted having ever met Madame de Montespan, however after her execution February 1680, her daughter Marguerite Monvoisin made several shocking revelations in prison. She claimed that Madame de Montespan had requested a Black Mass from La Voisin to win the favour of the King, before she became his mistress and thereafter she regularly contacted La Voisin whenever she encountered a problem that needed to be solved. According to Marguerite, her mother La Voisin also provided Madame de Montespan with love potions, with which she used to drug the King.

Regarding the death of Marie Angelique, Marguerite testified two accomplices Bertrand and Romani conspired with La Voisin on the orders of Madame de Montespan to poison Marie Angelique and the King. In 1681 Bertrand was accused of selling poison to Marie Angelique, while Romani was accused of delivering her gloves contaminated with poison, much like Catherine de Medici got rid of her rival Queen Jeanne of Navarre and Medea got rid of Glauke. The King was to be poisoned by a petition delivered into his hands, however La Voisin never managed to deliver it and her daughter Marguerite had burned it.

A servant in Marie Angelique’s household, Françoise Filastre, under torture claimed that Madame de Montespan had hired her to murder Marie Angelique, but just before her execution she recanted this allegation.

Author Anne Somerset, in her 2003-book, The Affair of the Poisons: Murder, Infanticide and Satanism in the court of King Louis XIV records that the King had instructed De la Reynie to keep all allegations regarding Madame de Montespan confidential. He was not even to disclose them to the other members of the special committee. As a preventative measure, the King then suspended the activities of the Chambe Ardente.

Neither Madame de Montespan, nor anyone else at court suspected that she was being investigated. By September 1680, the King continued to visit her on a daily basis, but he was always accompanied by another person. In the meantime, the King began visiting the governess of her children, Madame de Maintenon, who was older than him, very pious and apparently not very attractive.

On 21 July 1682, the King finally disbanded the Chambre Ardente and had the records sealed. Regarding the rest of the suspects, including Madame de Montespan, the Police Chief De la Reynie said: “the enormity of their crimes proved their safeguard.”

The Affair of the Poisons and the persecution of some members of the nobility effectively ended the overt poison epidemic in France. The Affair of the Poisons implicated 442 suspects: 367 orders of arrests were issued, of which 218 were carried out. Of the condemned, 36 were executed; five were sentenced to the galleys and 23 into exile. This excludes those who died in custody by torture or suicide.

Aftermath: Madame de Montespan’s conscience

Oblivious of the hornets’ nest that had broken over her head – and that she might have lost her head – Madame de Montespan adapted to her new status of no longer being the King’s mistress, but still enjoyed privileges at court, for she was the mother of his children. The atmosphere between her and her former employee, Madame de Maintenon remained icy and her continuous barbs against the former governess, irritated the King.

In July 1683 when Queen Marie Therese passed away, Madame de Montespan – as the Queen’s lady-in-waiting – found herself redundant at court. Unbeknown to her – and the rest of the court – six months after the Queen’s demise, the King secretly married Madame de Maintenon in January 1684. By December that year, the King moved Madame de Montespan out of her apartments adjoining his at Versailles, to a ground floor apartment. She took umbrage and often went away from court visiting family members and health spa’s – although still in vigorous health she had apparently grown enormously overweight. Madame de Montespan donated her annual allowance from the King to charities and convents, set up orphanages and wore a hair shirt as penance and she even restricted her diet.

In 1700, she acquired the Château d’Oiron and took occupation in 1704. She requested her friends not to write to her about news from the court as she no longer had an interest in such matters. She wrote to a friend they must: ”guard against dying steeped in sin, for after death, those who had lived in forgetfulness of God and the Church will regret in vain their waste of time.” Athénaïs de Montespan died aged 67 in 1707. Hopefully her penance paid off and cleared her conscience. Some historians still believe she was guilty, but never charged.

Top image: Medea – Frederick Sandys (1866) (Public Domain)