Where the motive of the 17th-century Spana Prosecution poisoners was to rid themselves of their abusive husbands, there exists another class of poisoners – those who use poison for political advancement. Long before the Renaissance trio of Thofiania d’Adamo, Giullia Tofana and Gironima Spana concocted the arsenic-based Aqua Tofana, Rome’s most famous poisoner was Locusta, active during the last term of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty in the 1st century AD.

Agrippina the Younger

Julia Agrippina the Younger (6 November AD 15 – 23 March AD 59) was possibly the most noble-bred woman in ancient Roman history. She was the great granddaughter of Emperor Augustus, daughter of general Germanicus, sister to Emperor Caligula, wife to her uncle Emperor Claudius and mother of Emperor Nero.

There were rumours that Agrippina had poisoned her second husband Crispus to inherit his estate. Emperor Claudius had his wife Messalina executed for plotting against him. Since they were both single, the Senate pushed for the marriage between Agrippina and Claudius to end the feud between the Julian and Claudian branches. Thus, although it was considered incest, Agrippina became the wife of her uncle, Emperor Claudius on New Year’s Day in AD 49.

Earlier in her life astrologers predicted that her son would become Emperor and he would kill her. According to Tacitus, Agrippina’s reply was: “Let him kill me, provided he becomes emperor.” Powerful and ambitious to see her son Nero become Emperor, she eradicated all opponents. She had Marcus Junius Silanus, a potential rival to Nero, poisoned. She eventually persuaded Claudius to adopt Nero as his heir, in favour of his own son Britannicus. Yet Claudius regretted this decision and when his fickle favour fell upon Britannicus again, rumours had it that Agrippina had her husband Emperor Claudius poisoned with a plate of deadly mushrooms, supplied by Locusta, and just to make sure, the doctor used a poisoned feather to induce vomiting.

When Nero became Emperor, the young man resisted being ruled by his domineering mother, especially since she interfered in his love life, and when she turned her favours to his step-brother Britannicus it inspired Nero to have Britannicus killed. He consulted his mother’s trusted poisoner, Locusta but when Locusta’s poison was slow to work on a slave, Nero flogged her with his own hand and threatened her with immediate execution, whereupon she produced a quicker-acting poison. Britannicus was successfully poisoned during a banquet in AD 55 and Nero rewarded Locusta with a full pardon and large country estates, where he sent pupils to learn her craft. Nero is said to have had a perchance for cyanide to be administered by an enema to his enemies.

Nero tried to have his mother poisoned in three attempts, but she had cleverly prevented her death by taking the antidote in advance. When she survived a plot to sink her ship, Nero eventually had his mother Agrippina assassinated, trying to mask it as a suicide.

In all of this, Locusta played a pivotal role. She had a preference for Atropa belladonna as a poison. Atropa-derived poisons were commonly used in ancient Roman murders, and previous Empress Livia, the wife of Augustus, reportedly used them to murder her contemporaries. Rumours had it that Augustus insisted on only eating figs growing in his garden, to circumvent being poisoned and Livia had them all smeared with poison. When Augustus died, her son Tiberius became Emperor. It seems Agrippina had a lot to learn from her great-grandmother about interfering in Roman politics as an Empress, and the effectiveness of using poison to eliminate adversaries.

After Nero’s suicide, Locusta was condemned to die by Nero’s successor, the Emperor Galba. She was led in chains through the city and executed.

Lucrezia Borgia

Spinning the wheel of time to the late 15th and early 16th century, Lucrezia Borgia, illegitimate daughter of Pope Alexander VI, is generally still considered to be one history’s most famous poisoners – but was she? Perhaps she was just a political pawn on the chess board of her father and her influential brothers.

Lucrezia could certainly not be considered feebleminded. Besides being a beautiful blond, she was a thoroughly accomplished princess, fluent in Spanish, Catalan, Italian, and French, and she was literate in both Latin and Greek. She was a prize wife for any European monarch or prince, and her family exploited this virtue, as she was married no less than three times.

When Rodrigo became Pope Alexander VI, he needed allies in the powerful, princely families and founding dynasties of Italy. On 12 June 1493 in Rome he married his beautiful daughter to Giovanni Sforza. When he became superfluous, Lucrezia warned her husband of her family’s intention to execute him, and he fled Rome. When requested to annul the marriage, he accused Lucrezia of having incestuous relations with her father. Her father, the Pope, decreed that the marriage was never consummated and finally, after being bullied into submission by his family, Giovanni signed a confession of impotence and documents of annulment, before witnesses.

In 1498 Lucrezia was married to the Neapolitan Alfonso of Aragon, which made her Princess consort of Salerno. Alfonso fled Rome, but returned upon her insistence and was murdered in 1500, probably by her brother Cesare Borgia. Although it lasted only a few months, the marriage was consummated and Lucrezia gave birth to a boy Rodrigo of Aragon, shortly before his father’s demise. The boy died aged 12.

In 1502 Pope Alexander VI, married Lucrezia to Alfonso I d’Este, Duke of Ferrara. She bore him eight children during this marriage, and turned into an accomplished Renaissance duchess, effectively rising above her previous reputation and she outlived the fall of the Borgias, following her father’s demise. Pope Alexander was believed to have had a habit of poisoning cardinals to inherit their estates and it is suspected one night he drank the wrong bottle of wine.

According to Mandell Creighton in his History of the Papacy: “Lucrezia was personally popular through her beauty and her affability. Her long golden hair, her sweet childish face, her pleasant expression and her graceful ways, seem to have struck all who saw her.” Yet behind this beauty and innocence lay a tainted darker portrait of a woman embroiled in incest, poisoning and murder, probably conjured up by her family’s pollical enemies. There is no historical basis for the legend that she had a hollow ring that contained poison. Was she a poisoner?

Catherine de Medici

In neighbouring France, a sensational historical poisoning drama unfolded around another Italian-born princess, Catherine de Medici, born two months before Lucrecia’s death in 1519, who became Queen of France from 1547 to 1559 by marriage to King Henry II and the mother to French kings Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III.

Upon the order of her uncle Pope Clemment, fourteen-year old Catherine married prince Henry, second son of King Francis of France in October 1533. In 1536, prince Henry’s older brother and heir to the throne, 18-year old Francis, asked for a cup of water after playing a round of tennis. The water was brought to him by his secretary, Count Montecuccoli. Shortly after drinking it, Francis collapsed and died several days later. Immediately it was suspected that he had died of poisoning, but by whom? When Montecuccoli’s quarters were searched, a book detailing several types of poison was discovered and under torture, Montecuccoli confessed to poisoning the Dauphin and was subsequently executed. Montecuccoli had been brought to the court by Catherine, and at the time of the Dauphin’s death, she was already known for having an interest in poisons and the occult.

Thus when King Francis I died in 1549 and the Dauphin already eliminated, Henry and Catherine became King and Queen of France. Yet King Henry II had no interest in Catherine and favoured his mistress Diane of Poitiers. Eventually, since France needed an heir, after ten years of marriage and bearing the humiliation of not being able to conceive and fulfil her duties as Queen, in 1544 Henry II and Catherine’s son, the first of ten children, was born.

Unlike Agrippina who had to scheme to secure the throne of Rome for her son Nero, Catherine’s sons were already bloodline legitimate heirs to the throne of King Henry II. However, the Guise faction, cousins to the king, laid claim to the throne and throughout her reign, Catherine had to fight teeth and claw to keep the Valois bloodline on the throne. Ironically, the Duke of Guise, Francois Lorraine, through his maternal line, was a descendant of Lucrezia Borgia. Another threat to the throne came from the Protestants, led by the Bourbons of Navarre.

King Henry II’s sudden accidental death during a joisting tournament in 1559, cast 40-year old Catherine, who had not been allowed to meddle in state affairs by her husband the king, in the role of Queen mother to 15-year-old Francis II, who a year prior had been married to Marie Queen of Scots, niece to the Duke of Guise. Scarcely a year later on 5 December 1560, King Francis II died and, the Privy Council appointed Catherine as governor of France – regent for 10-year old Charles IX.

At this stage young prince Henry of Navarre, son of King Antoine de Bourbon and Queen Jeanne d’Albret III of Navarre lived in the household of Catherine, his godmother. Their destinies were to become entwined in an unexpected twist. Unbeknown to Catherine, beside her sons, she was raising a future great Protestant King of France.

By 1553 France’s religious wars had escalated, due to the Duke of Guise being assassinated. Not only did Catholic Queen Catherine have a rival in Protestant Queen Jeanne of Navarre but Queen Elizabeth I of England, who had supported the Protestants financially, stepped up and sent troops, primarily due to concerns over the spread of Catholicism and a potential Spanish expansion.

In 1563 Catherine’s son King Charles IX became of age, but Catherine did not surrender her reign and dominated her son in affairs of the state. In 1567 the Protestant Huguenots retreated to the fortified stronghold of La Rochelle under leadership of Queen Jeanne of Navarre, now widow of Catherine’s former ally Antoine de Bourbon. Jeanne’s 15-year-old son, Henry III of Navarre joined her. Henry had deserted Catherine’s court in favour of his Hugenot Queen mother Jeanne.

“We have come to the determination to die, all of us“, Jeanne wrote to Catherine, “rather than abandon our God, and our religion”. Catherine called Jeanne, whose decision to rebel posed a dynastic threat to the Valois, “the most shameless woman in the world“.

Despite despising Jeanne, Catherine desired a marriage between her daughter Margaret and Henry III of Navarre, Jeanne’s son, with the aim of uniting Valois and Bourbon interests. Margaret, the intended bride however, had an affair with Henry of Guise, the son of the late Duke of Guise. When Catherine found this out, she had her daughter dragged from her bed by her hair and together with her son King Charles they beat her, ripping her nightclothes.

Eventually Queen Jeanne of Navarre acquiesced to the marriage, provided her son Henry could remain a Hugenot. The wedding entourage arrived in Paris in June 1572 to shop for clothes for the pending wedding. It is alleged that Catherine had arranged with her personal perfumier to sell poisoned gloves to Queen Jeanne who died shortly after. The groom, Henry become King Henry III of Navarre.

Despite Queen Jeanne’s death and the suspicions that she had been murdered on the orders of Catherine, the wedding still took place in August 1572. Margaret had to be dragged to the pulpit. Three days after the wedding Admiral Coligny, a Hugenot general was assassinated, igniting the St Bartholomew Massacre in Paris, which soon spread through the rest of France and thousands of Hugenots were killed. King Henry of Navarre was forced to convert to Catholicism to save his life – he is reported to have stated: “Paris is well worth a mass.”

Two years later in 1574 King Charles died and Catherine’s favourite son, Henry the Duke of Anjou became king. When Catherine’s youngest son, Francis Duke of Alencon died of consumption in 1584, it meant Catherine de Medici had run out of sons for the crown, for King Henry III had no heirs.

Catherine fell ill and was confined to her rooms in the Chateau de Blois. What she did not know was that on 23 December 1588, King Henry III had the Duke of Guise and eight members of the Guise family hacked to death in the dungeon far below her bedroom. A few days later she was informed and Catherine de Medici died on 5 January 1589, at the age of sixty-nine.

At Chateau de Blois, where she died, in Catherine’s personal work room 237 small wooden cabinets were discovered and described as her private apothecary where she could have kept her extensive collection of poisons. Yet historians are of the opinion that she could have used these for personal correspondence.

Eight months after Catherine’s death, King Henry III was assassinated. Since there were no legitimate heirs to the Valois, the crown went to King Henry of Navarre, husband of Margaret, who became King Henry IV of France and he reverted back to being a Protestant.

Henry IV said of Catherine: “I ask you, what could a woman do, left by the death of her husband with five little children on her arms, and two families of France who were thinking of grasping the crown—our own [the Bourbons] and the Guises? Was she not compelled to play strange parts to deceive first one and then the other, in order to guard, as she did, her sons, who successively reigned through the wise conduct of that shrewd woman? I am surprised that she never did worst.” Remarkable words from a man about a woman suspected of poisoning his mother. More remarkable, as a Protestant he was entitled to and indeed divorced his wife, Margaret, only to marry Marie de Medici, a younger relative of Catherine, to settle his war debt owed to her father.

Were Lucrezia Borgia and Catherine de Medici poisoners or not? In a previous article I discussed that up until the 19th century it was virtually impossible to scientifically prove that someone had consumed poison, and it was even more difficult to prove who had administered the poison. The Spana Prosecution in Italy a century prior proved poisons such as Aqua Tofana were freely available over Europe.

South African researchers F.P Retief, and L Cilliers, in their 2000 -article Poisoning during the Renaissance: The Medicis and the Borgias, published by The Southern African Society for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (SASMARS) summarize the backdrop of the accusations against these two influential Renaissance families: “Our assessment of the extent and nature of their poisoning showed that they were indeed products of an era characterized by intrigue, violence and assassination but that their roles as poisoners have probably been exaggerated. Knowledge of poisons had improved little since Roman times and there was still a close association between witchcraft, sorcery and poisoning but arsenic had become the most popular poison. An absolute inability to detect human poisoning chemically before the eighteenth century added to uncertainty, suspicion and common accusations of suspected poisoning, which could subsequently not be proved or disproved in the majority of cases. There is limited evidence of Medici involvement in poisoning, with the possible exception of Catherine de Medici, Queen of France, who collected poisons, frequented astrologers, wizards, and known poisoners, and could well have poisoned a limited number of her enemies. One prominent Medici, Ipolito, died of poisoning. The Borgias were involved more directly, although even here their legendary prowess with cantarell powders (probably arsenical compounds) is probably much overstated. Pope Alexander VI (Rodrigo Borgia) had a reputation of inter alia poisoning five of his cardinals for their wealth; there may be truth in some of these allegations. His illegitimate son, Cesare Borgia, was ruthlessly ambitious, but his many victims died of strangling and stabbing rather than poisoning. The infamous Lucrezia Borgia (sister of Cesare) was a pawn in the power of her father and brother, and not a significant poisoner.”

Historians warn that the reputations of Lucrezia and Catherine could be tainted due to misogyny. Not being able to prove that Lucrezia Borgia and Catherine de Medici were poisoners does not mean they were not. Are we more likely to believe Lucrezia was not because she was described as angelic and Catherine was because she was described as the “Serpent Queen”? What is true for Livia, Agrippina, Lucrecia and Catherine are that they were royalty and although suspected, they were not persecuted for poisoning their adversaries – there was simply not enough proof, but this did not exempt the commoners like Locusta and the poisoners of the Spana Prosecution. During the following century, the Affair of the Poisoners, rocked the court of King Louis XIV of France and this time, noble ladies were not spared from prosecution.

An interesting fact: When Claire Booth Luce was the United States ambassador to Italy, from 1953 to 1956, she became a victim of arsenic poisoning because of the continual flaking of an arsenic-based paint from the embassy dining room ceiling onto her dinners. She was forced to resign her position because of ill health brought on by that exposure.

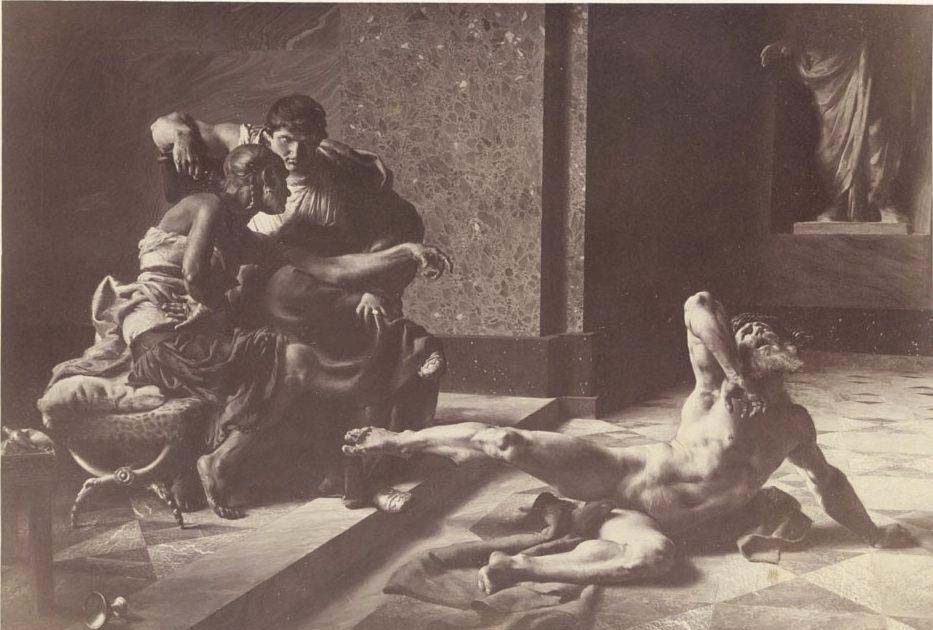

Top image: A Glass of Wine with Lucrezia Borgia standing by her father Pope Alexander VI, by John Collier (1893) (Public Domain)