The standard answer “I bought the poison for rats” alerts experienced detectives to “smell a rat” and investigate female poisoners.

Rats are commensal, benefitting from human proximity. They evolved millions of years ago in Asia and moved in with humans, for humans provided a readily available source of food, whether their crops, their granaries or their pantries at home. From medieval times to the Victorian era Chasseurs de Rats or Rat Catching was an honourable and profitable occupation.

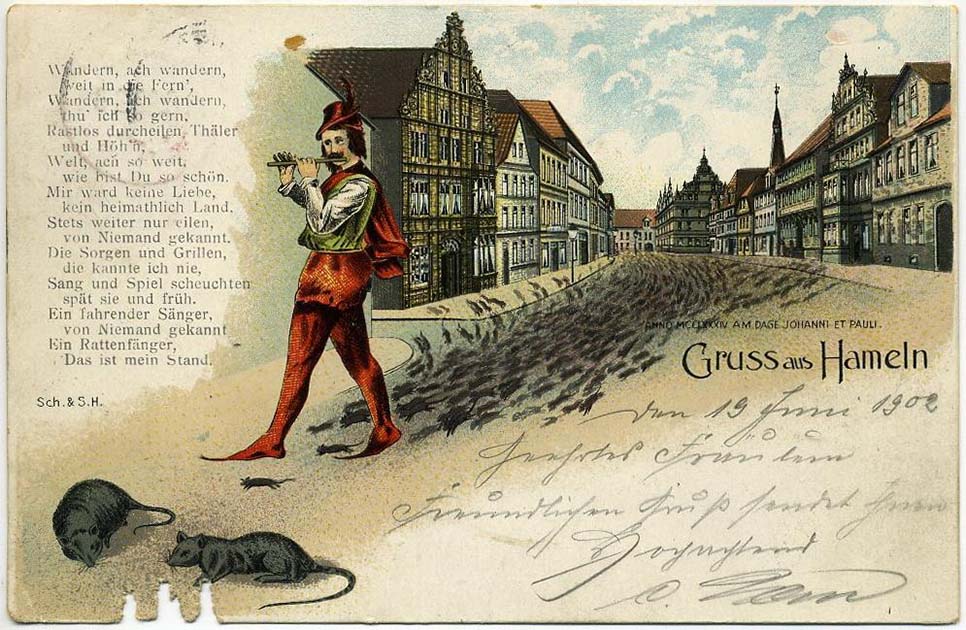

The Pied Piper or Rat Catcher of Hamelin is originally a 13th-century fictional tale of the importance of such a character. Rats – or at least the fleas on rats – are responsible for plagues decimating the populations of China, Asia, Europe and the America’s for centuries and rat catchers provided an invaluable service by catching them.

Queen Victoria had her own personal rat catcher, called Jack Black. It was during her reign that the Arsenic Act or the Sale of Arsenic Regulation Act was passed in 1851. Arsenic by then was widely used in many products including cosmetics, medicine and stimulants, but also as dyes in wallpaper and paints. After the toxicity of arsenic became widely known, these chemicals were used less often as pigments and more often as insecticides.

The Sale of Arsenic Act of 1851 required those selling arsenic to maintain a register of those who purchased it, including the quantity and its stated purpose. It also required for it to be coloured with soot or indigo, unless the arsenic was to be used for a purpose that would make such treatment unsuitable, for example in medical or agricultural applications. Now at least a colour could be recognized, but it remained colourless for agricultural purposes, so poisoners always claimed they bought the poison to kill rats for agricultural purposes.

Rat Poison

Rodenticide is the collective name for chemicals killing rodents, commonly known as rat poison. Rats cannot vomit. Anyone with a rat in the house will notice telltale evidence that rats nibble at food first before eating all of it. Rats are clever and have learnt to smell, nibble and wait to see if the food is edible or not. This phenomenon is called poison shyness. Animals learn an association between stimulus characteristics, usually the taste or odour, of a toxic substance and the illness it produces and this allows them to detect and avoid the substance.

It seems that, unlike animals, humans have lost their survival mechanism of poison shyness.

In the 1660’s in Renaissance Italy, Thofania d’Adamo had concocted the original recipe for Aqua Tofana – this arsenic-based poison was colourless and tasteless.

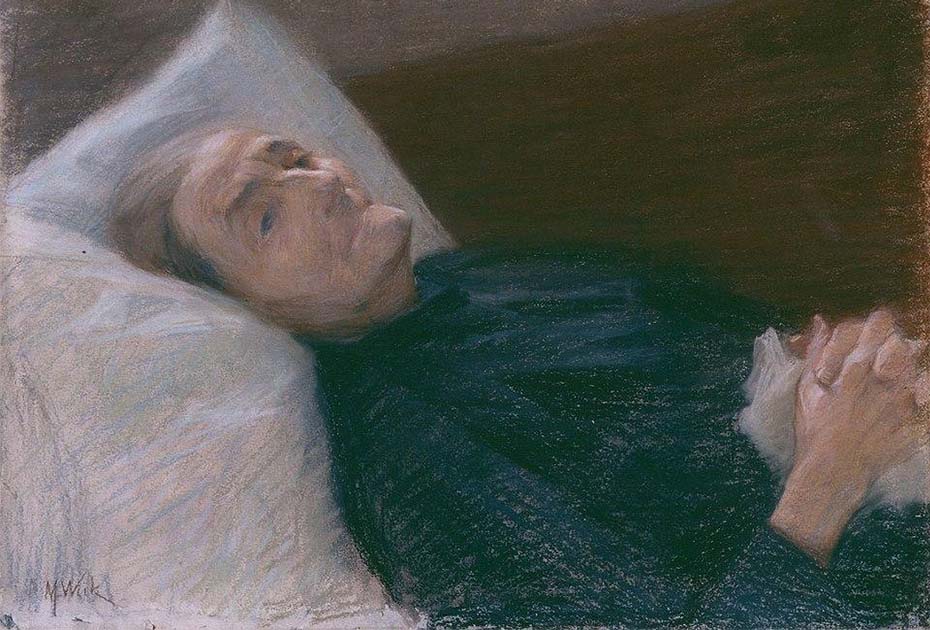

What concerns me when I read case studies about female poisoners is that despite glaring symptoms, physicians are often blind to the possibility that someone has been poisoned, either by a discontented wife, or by a seemingly sweet caring wife. It also amazes me that the victims do not suspect they have been poisoned. Arsenic poisoning was often misdiagnosed as cholera, liver diseases, and a variety of other illnesses.

Symptoms of arsenic poisoning over a brief period of time, may include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and a watery diarrhoea containing blood starting within hours of consumption. If anyone experiences these symptoms they should request a simple test. Tests are available by measuring arsenic in blood, urine, hair, and fingernails. The urine test is the most reliable test for arsenic exposure within the last few days. Urine testing needs to be done within 24 to 48 hours for an accurate analysis of an acute exposure. Tests on hair and fingernails can measure exposure to high levels of arsenic over the previous 6 to 12 months.

American Rebecca Copin 1835

Women often offer an excuse that they poisoned their husbands because they abused them. However in one of the earliest documented cases of domestic violence in America, the complainant was a man. In 1835 John Copin of Kanawha, Virginia, filed for divorce due to domestic violence. His wife Rebecca scalded him with boiling water, threatened to shoot him, beat him with his own crutches when his leg was broken and attempted to poison him with arsenic.

Rebecca Copin’s case is one of the earliest documented cases of attempted murder by a wife of her husband using arsenic in the United States. While the jury found that Rebecca Copin had indeed tried to murder John Copin, his petition for divorce was not granted.

South African Theresa May Hall 1986

When Theresa May Hall nee Peyper was five years old, her father died and her mother moved back to Theresa’s grandparents, but she placed her and her siblings in a home.

Upon completing grade 11 Theresa began taking care of her mother, Rhoda Dora Peyper. Theresa married Frank Ernest Hall, a man 33 years her senior and ten years older than her mother. For 17 years, Theresa took care of her elderly husband and mother, until one day she decided she had had enough.

By the end of 1985, Theresa asked the caretaker, Mrs Heila Gericke for some rat poison, to kill the rats at the dustbins, and there was a rat in her apartment. Mrs Gericke offered her a mousetrap, but Theresa said she would buy rat poison elsewhere. She bought a bottle of arsenic at the pharmacy in Plein Street and from January 1986 she systematically began administering arsenic to her husband’s brandy.

When 81-year old cantankerous Frank was admitted to hospital, fellow patients observed Theresa’s unsympathetic attitude towards him, although she regularly brought him brandy in a flask – laced with poison. On the evening of 25 March 1986, Theresa was overheard telling her husband: “I’ll just give you arsenic to shut you up for ever.” A few hours later, Frank died. The postmortem revealed that Frank had died of senility, pneumonia, a broken hip and arsenic poisoning.

Next on her list was her mother, 70-year-old Rhoda Peyper. She had undergone two eye surgeries and complained to Theresa about the pain and the discomfort. Theresa decided to solve the problem by administering arsenic to her mother’s tea.

Ten months after Frank’s death, the police came knocking at Theresa’s door. Theresa had made a fatal mistake. She blatantly offered to bake Warrant Officer Jan Kock a cake and joked there would be no arsenic in it. He collected the flask she used to take the brandy to hospital, but analysts could not find traces of arsenic in the flask. The offer to bake him a cake raised Warrant Officer Jan Kock’s suspicion and he returned to Theresa’s apartment, where he seized everything in her kitchen. Arsenic was found in the baking powder.

Warrant officer Jan arrested Theresa on 3 February 1987 and Mr Justice Irvin Steyn presided over her trial. Theresa claimed Frank had bought the arsenic to commit suicide, and requested her to administer the final dose of arsenic to him and she complied. Her neighbour confirmed she bought it to get rid of the rats. Of her mother, Theresa said that she suffered much since her eye surgeries and she administered the arsenic in her tea to relieve her pain. Rhoda Peyper’s health improved remarkably after she moved in with her younger daughter, Mrs Ellen Martins, after Theresa’s arrest.

Mr Justice Steyn sentenced Theresa, aged 48 at that stage, to seven years for the murder and another consecutive seven years for the attempted murder of her mother. Effectively she had to serve 14 years. Shortly after the sentencing, Theresa phoned her mother. She first inquired about her health and then told her about the sentence. Rhoda Peyper said she harboured no grudges against her daughter.

At that stage, Theresa Hall was the only woman in South Africa that escaped the death sentence for poisoning, since it could not be proved beyond reasonable doubt that Frank had been poisoned. The judge could not find a motive for the crimes, besides the fact that Theresa May Hall was “sick and tired of old people.”

Almost a century before Theresa May Hall poisoned her husband and mother, Lydia Sherman nee Danbury of Derby, Connecticut poisoned her three husbands, and five children. In 1864, after being married for 23 years, 40-year old Lydia poisoned her first husband Edward Struck with arsenic because he became depressed after losing his job. She also poisoned three of her own young children and two more children. She married her second husband, the widower Dennis Hurlburt, in 1868, but when his health declined, she poisoned him with arsenic. Ironically, she was working as a nurse, tending to sick people. She married Horatio Sherman in 1870 and killed him in May 1871. She was convicted of second-degree murder in 1872. After five years of serving her sentence, she managed to escape and found employment as a housekeeper. Luckily she was re-arrested before she could kill her employer. It seems Lydia Sherman was also just “sick and tired” of her family.” She died in prison in 1878.

South African Unita Hendrietta Green 2000

Fifty-one-year old Unita Green led a lonely, isolated life with her long-time lover, 57-year-old Gert van Rensburg on the farm Doornrivier in the Zeerust district. No neighbour, friend or confidant would listen to her complaints about her lover’s alcohol and drug abuse and his affairs. The only solution she could think of, was to get rid of Gert. So Unita laced his tomato and onion sandwich with Temic, a rat poison. Gert died in the bed right next to her in February 2000, but Unita just rolled over, cuddled behind the dead man’s back and slept.

The next morning she was faced with a conundrum. She had to get rid of the body. She dragged him to the kitchen and shoved his body, headfirst into the freezer. While pondering what to do next, Unita stroked the head of her dead lover in the freezer. She quickly closed the lid when the owner of the farm, Mr Wouter Kirstein arrived, she asked Wouter to bring her petrol from town. He obliged.

On the Friday night, Unita switched off the freezer and removed the body. She drenched the body, blankets and clothing with the petrol and set it to light. While Gert burned on his pyre, she talked to him and told him she would scatter his ashes in the veld, so he could return peacefully to nature. When the fire turned to ashes, Unita noticed Gert’s skull was still discernible. She cut it off with a knife and fried it over the coals. She kept her promise to Gert and scattered some of his remains in the veld. The rest of the charred body, she crammed into a suitcase and dropped it into a cattle dip.

Police investigated Gert van Rensburg as a missing person and eventually arrested Unita for murder. On 5 May 2001, Mr Justice NJ Coetzee sentenced her to life.

The reasons why abused women stay in abusive relationships will be discussed in a later article. Please contact relevant NGO’s or safe houses for assistance.

Chasseurs de Rats

Were these women who bought rat poison Chasseuses de Rats? No. The true Chasseurs de Rats were the detectives who did not suffer from poison shyness. They smelled a rat and diligently did their work.

Although they may be deceased, let us pay tribute to the Rat Catchers: Warrant officer Jan Kock, who did not eat Theresa May Hall’s poisoned cake; Constable Petrus Rheeder who arrested Margaret Rheeder; Colonel Fred van Niekerk who painstakingly built his case against Maria Lee and Captain Marelise van Zijl who took Letitia Erasmus’s confession.

And kudos to those detectives, physicians, relatives and victims who smell a rat and act pro-actively.

Top image: Two rats by Vincent van Gogh (1884) (Public Domain)

By Dr Micki Pistorius