Ironically the word ‘arsenic’ originates from Greek folk etymology as ‘arsenikon’, a neuter form of the Greek adjective ‘arsenikos’ meaning “male”, or “virile” and over centuries it was arsenic that women have been using to eliminate the males in their lives.

In the mid 1600’s a trio of Renaissance Italian woman with a keen sense for enterprise, identified a gap in the market and sold a poison called Aqua Tofana to women who wanted to rid themselves of their abusive and inconvenient, cumbersome husbands. Thofania d’Adamo had concocted the original recipe for the poison with an arsenic base, thus the name Aqua Tofana.

Thofania d’Adamo detested her husband Francesco d’Adamo and like so many wives in similar circumstances the thought of getting rid of him invaded her mind. In psychology today, this would be referred to as pervasive homicidal thoughts. Once she set her mind to the task, she developed a slow-releasing poison, colloquially dubbed Aqua Tofana. Since she was successful in her endeavour, Thofania decided more women could benefit from her innovation to rid themselves of troublesome husbands and she began producing and discreetly marketing the concoction, which soon became very popular all over Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

A blend of arsenic, lead, and possibly belladonna produced a colourless and tasteless lethal liquid, easily mixed with water or wine and instructed to be served during meals, to deliver the desired results over a period of days. Since it was slow-releasing, it was difficult to detect and its symptoms would resemble a progressive disease or other natural causes. The first small dosage would produce cold-like symptoms, but by the third dose the symptoms included vomiting, dehydration, diarrhoea, and a burning sensation in the throat and stomach. The fourth dose would be lethal. The added benefit of a slow-release poison was that it afforded the victims time to write their will. The antidote was vinegar and lemon juice, if a will was not timeously produced, but this was seldom administered.

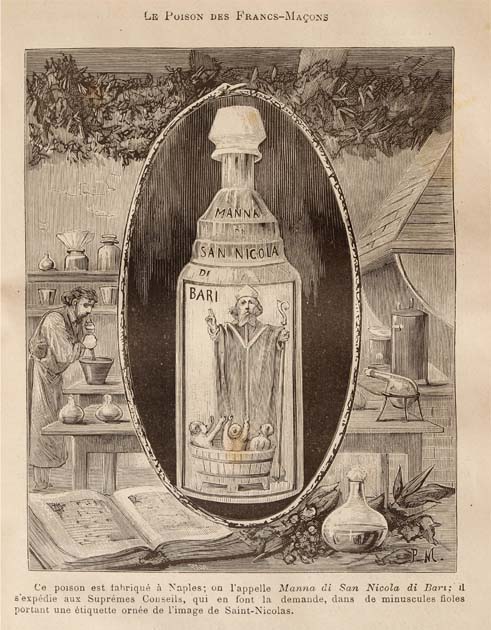

Aqua Tofana was dispensed into vials and labelled “Manna di San Nicola” (“Manna of St. Nicholas of Bari”), fooling custom officers and authorities into believing it to be a cosmetic product or a devotional artifact. It is estimated over decades more than 600 victims died from this poison, mostly husbands. Thofania Adamo was executed for poisoning her husband in July 1633, but she left a lethal legacy.

Pre-empting the Tupperware sales parties by a few centuries, one of her disciples, Giulia Mangiardi, code named Giulia Tofana, fled to Rome after Thofania’s execution and set up a circle who sold the poison on to their eager customers. Giulia was so discreet she was never detected and she died peacefully in her sleep in 1651. One wonders if her afterlife was so peaceful? Where Giulia was described as nasty, ugly and raggedly, her stepdaughter Gironima Spana was pleasant, respectable and intelligent.

Gironima Spana expanded her stepmother Giulia’s circle into a more formal network of poisoners operating clandestinely in Rome, including some aristocrats, who would often sent carriages to fetch her. Gironima doubled up as a successful astrologer, often entertaining the ladies in their salons. Since women were forbidden to buy poison, the poisoners enlisted a priest Padre Don Girolamo as interlocutor, who bought the poisonous ingredients from his brother, an Apotheker.

One of the co-conspirators, Giovanna De Grandis, originally a laundress, soon became the confidante of Gironima, who shared with her the secret recipe to make the poison. On 31 January 1659 Giovanna was caught red-handed and her arrest led to the uncovering of a major crime syndicate, run by women. Under the leadership of lieutenant governor Stefano Bracchi, the investigation uncovered more than 40 people, including members of the nobility, entangled in the poison-for-sale network. Gironima Spana steadfastly denied her involvement, even in the face of her accomplices’ and clients’ accusations. Finally on 20 June 1659 she signed a full confession.

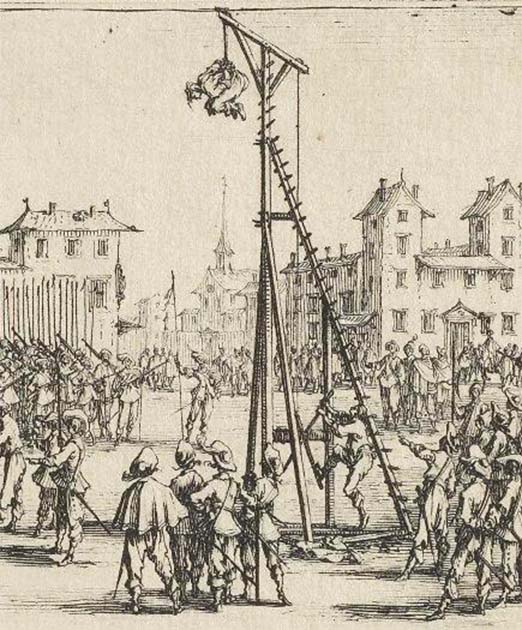

One by one, as they were implicated, the women were imprisoned in the Papal prison of Tor di Nona for questioning. Some of them were tortured in the form of the strappado, where the person’s hands are tied behind their back and they are suspended by a rope attached to the wrists, typically resulting in dislocated shoulders.

Of course, members of the nobility were spared. In exchange for a confession, they were granted Papal immunity. Anna Maria Conti confessed to having poisoned her abusive husband, for she suspected him of poisoning her father. She was not prosecuted, but her maid, Benedetta Merlini, who had introduced Anna Maria Conti to the poison-sellers, was arrested, imprisoned and tortured in Tor di Nona.

Anna Maria Caterina Aldobrandini accused of having poisoned her husband, Francesco Maria, the Duke of Cesi in 1657 was never charged. Maddalena, signora, the wife of cardinal vicar’s chief of police, who had bought poison from Cecilia Gentili, escaped arrest by virtue of her husband’s position. One wonders if the chief of police ever suspected his wife was plotting to murder him? Gironima Spana’s maid Francesca Flore confessed she had sold poison to Sulpizia Vitelleschi, an Italian heiress and the richest woman in Rome, who used it to poison her husband. Since her husband was still very much alive, Sulpizia was not persecuted, but due to her rank it was decided not to investigate the dubious death of her first husband.

The Spana Prosecution, a major trial lasting from January 1659 to March 1660 shook the foundations of the Roman society and the Papal States. The five main perpetrators Gironima Spana, Giovanna De Grandis, Maria Spinola, Graziosa Farina, and Laura Crispoldi were executed at the Campo de’ Fiori in Rome on 5 July 1659. Cecili Verzellina was hanged on 6 March 1660 and on the same day, Teresa Verzellina, Benedetta Merlini and Cecilia Gentili were flogged through the streets and exiled.

Pope Alexander VII ordered the records of the trial to be sealed at the Castel Sant’Angelo, since he wished to avoid spreading knowledge about the poison and the bad example of the women. Typically, a legend was soon spun in the mediocre, bored and impressionable minds of the population about an organization of female serial killers who murdered hundreds of husbands until they were caught in a trap by a Papal governor.

Was there a gang of renegade female serial killers running around Rome killing hundreds of husbands?

The social acceptance of wife beating can be traced back to 753 BC under the rule of Romulus, the first King of Rome. The Laws of Chastisement deemed wife beating legal so long as the rod or stick being used for physical discipline had a circumference no bigger than the girth of the base of the man’s right thumb, known as “The Rule of Thumb.”

This continued to be the trend to the extent that the 14th century Roman Catholic Church encouraged husbands to beat their wives out of concern for their spiritual well-being and it was certainly still prevalent when Pope Alexander VII occupied the ‘sedia gestatoria’.

Although Pope Alexander VII had sealed the records, the archives were discovered again in the 1880s in the Archivo di Stato. From the records it emerged Ginonima Spana was an astronomer, Giovanna De Grandis was a laundress and Benedetta Merlini and Francesca Flore were maids. One can surmise that the majority of the women were the wives of tradesmen. Looking at the trades of their husbands, the men were a barber, sieve maker, painter, inn keeper, gilder, butcher, cloth cutter, tailor, dyer, linen draper, butler, mattress maker and a soldier. None of these trades would have had pensions or life insurance. These married women did not kill their husbands for financial inheritance – as the Black Widows do, nor were they Angels of Death or Angels of Mercy. They were ordinary women, who had had enough of abusive husbands, “disciplining” or “chastising” them. Divorce was not an option for these women – especially not in a Roman Catholic state. So, the only solution in their minds was to discretely kill their abusive husbands. That is it – they were not serial killers at all.

Perhaps in the Afterlife, Thofania d’Adamo, Giulia Tofana and Gironima Spana joined the Greek mythological Danaids, the 50 daughters of Danaus, King of Libya, who were ordered by their father to kill their 50 husbands on their wedding night. All but one, complied. Hypermnestra, spared her husband Lynceus because he respected her desire to remain a virgin. The rest were condemned to spend eternity carrying water in a sieve to fill a tub, so they could cleanse themselves of their sins. The tub would never be filled, exemplifying the futility of the act of murdering their husbands.

One wonders if the Danaids are responsible for contaminating drinking water with arsenic? It is alarming to know that through contaminated drinking water, more than 200 million people globally are exposed to higher-than-safe levels of arsenic.

Top image: Laus Veneris by Edward Burne-Jones: (1875) (Public Domain)